1Choctaw Beer

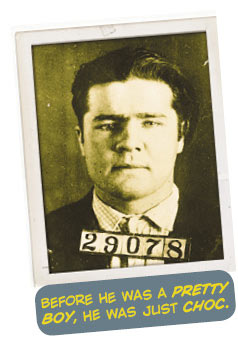

Before he was known across the country as Pretty Boy Floyd, the outlaw Charles Floyd was known in his Eastern Oklahoma hometown as “Choc.”

This came from the fact that the young Floyd had a powerful taste for Choctaw beer, called “choc” for short. In Clint Eastwood’s classic western movie The Outlaw Josey Wales, a nervous trading post proprietor tells Wales, “I’ve got some beer. Some good-brewed choc. It’s on the house.” The term “Choctaw beer” or “choc” appears frequently in the Western and outlaw literature of the late-19th and early-20th centuries, but few today remember what it was.

This came from the fact that the young Floyd had a powerful taste for Choctaw beer, called “choc” for short. In Clint Eastwood’s classic western movie The Outlaw Josey Wales, a nervous trading post proprietor tells Wales, “I’ve got some beer. Some good-brewed choc. It’s on the house.” The term “Choctaw beer” or “choc” appears frequently in the Western and outlaw literature of the late-19th and early-20th centuries, but few today remember what it was.

Choctaw beer is not a brand, but rather a term for a distinct tradition of illegal, self-manufactured beer, just as moonshine or white lightning are terms for a distinct tradition of illegal, self-manufactured corn liquor. Aside from white lightning, Choctaw beer was the most iconic—and roughest—alcoholic beverage of the old West. As an Oklahoma newspaper remarked in 1906: “A few swigs of the stuff will make an ordinary cottontail rabbit spit in the face of a bulldog.”

The beer is named for its creators, the Choctaw Indians of Oklahoma. The Choctaw are indigenous to the Southeastern United States, but the majority of them were forcibly removed to Indian Territory (in current-day Oklahoma) by the federal government following the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The act violated previous treaties with the Choctaws and other tribes and culminated in the infamous Trail of Tears. Nearly 2,500 Choctaws died during this brutal deportation from their homeland. Eventually the Choctaws settled in their new homeland, which now encompassed the southeastern corner of Indian Territory.

Among other regulations, federal law prohibited the importation of alcohol into Indian Territory, and internal tribal laws reinforced this policy. It isn’t exactly clear when Choctaw families began manufacturing their namesake beer, but the homebrew tradition was firmly established on the farms of the Choctaw Nation by the mid-19th century.

When the railroads began stretching westward across the U.S. in the 1870s, railroad workers poured into the Choctaw Nation, soon followed by coal miners. In the 1955 edition of the Chronicles of Oklahoma, Stanley Clark writes, “These men were of American, English, Irish, Scotch and Welsh descent mainly from the coal fields of Pennsylvania. The first Italians recruited for the mines arrived at McAlester in 1874; by 1883 it was estimated 300 families were in the Krebs-McAlester area. Lithuanians in 1875 and Slovaks in 1883 were brought from the coal fields of Illinois and Pennsylvania.”

It’s rough work, gouging coal from the bowels of the earth, so when they finished their long shifts the miners naturally wanted a drink. Unfortunately, the mines were located in Indian Territory. There were none of the saloons that dotted the rest of the West, and unlike with the coal fields of West Virginia and Kentucky, there were no whiskey stills hidden in adjacent hills. So the miners purchased Choctaw beer from the locals. A 1909 edition of The American Brewers’ Review states, “In the mining region many of the miners are Hungarians, Poles, Irish, Italians, and Mexicans. They like Choctaw beer and often drink it to excess.”

In 1889, the Oklahoma Territory was opened to white settlement. The ensuing land rush overwhelmed the Choctaw Nation. The besieged tribe suffered thefts, violent crimes and murders at the hands of whites and other tribal members.

In 1889, the Oklahoma Territory was opened to white settlement. The ensuing land rush overwhelmed the Choctaw Nation. The besieged tribe suffered thefts, violent crimes and murders at the hands of whites and other tribal members.

Among other results, this invasion increased the demand for Choctaw beer. Steven L. Sewell, who explored the history of Choctaw beer in an article for the Journal of Cultural Geography, writes, “Because most men spent much of their time down in the mines, women dominated the Choctaw beer industry.” While there were eventually brands of bottled, locally-distributed Choctaw beer, much of the trade was individual women making and selling their own concoctions. During these hard times, the choc trade was an economic necessity for many families.

The federal authorities were never happy with the widespread Choctaw beer trade. During the 1890s a series of contradictory rulings confused the issue of whether the territorial alcohol ban applied to beer or only hard liquor, whether the ban applied to U.S. citizens or only to tribal citizens, and whether the ban covered the manufacture of alcohol in Indian Territory or only the importation of alcohol into Indian Territory. Congress eventually clarified the issue with anti-beer legislation, but the temporary gray areas had helped choc brewers to flourish and gain a solid foothold. Local authorities were easily bribed, and when they weren’t, the risk of 30 days in jail wasn’t a serious deterrent to a profitable choc operation. There were also semi-legal workarounds—many sold Choctaw beer under the guise of a medicinal tonic, and local doctors attested to the health benefits of choc, arguing that it was healthier than the local water.

When Oklahoma joined the United States in 1907 it was as a “dry state,” a designation which had little effect on the underground choc trade. When drinkers in other states began to deal with the predations of Prohibition a dozen years later, Oklahoma’s drinkers were already decades deep into their love affair with illegal Choctaw beer.

“Choctaw beer was an important part of the culture of the Choctaw Nation,” writes Sewell. “While ‘choc’ originated with the Choctaws, it quickly became the favorite drink of every nationality and ethnic group in the Choctaw Nation.” Shortly after their arrival, Poles, Italians, and members of other immigrant groups had begun to not only guzzle choc, but manufacture and sell it as well. Residents of the Choctaw Nation area and the entire state of Oklahoma became fiercely loyal to the beverage. The Oklahoma Historical Society records an anonymous state resident of the mid-20th century as saying, “It won’t hurt nobody cause fruit’s good for ya, but it’ll make you drunker than a fool. Don’t put snuff in it, that would kill a dog! As good as it is, everybody should have two or three glasses a day. My family always felt good.”

There was a kick to choc that high alcohol content alone couldn’t explain, and the frequent addition of snuff and other forms of tobacco was probably a big part of it. The American Brewer’s Review asserted that “cocaine and other injurious drugs” were often added, but it’s unlikely that rural home brewers were spiking their choc with coke. However, fishberries (also known as Indian berries, or anamirta cocculus) were a common choc ingredient. Fishberries contain a powerful poison, and their primary use is stunning fish so they can be easily scooped up in a net.

Tobacco, “injurious drugs,” and fishberries aside, the basic ingredients of choc were what you’d expect from homebrewed beer: hops, barley malt, sugar, and yeast. Depending on the brewer—and what happened to be on hand—other grains or fruits such as oats, rice, corn, apples, peaches, and raisins could and would be thrown in as well.

In 1933 Congress passed the 21st Amendment, repealing Prohibition. Rather than returning completely to its own strict prohibition policies, the state of Oklahoma decided to allow the sale of 3.2 beer. While it is practically impossible to get drunk off of 3.2 beer, this decision signaled the slow decline of Choctaw beer in Oklahoma. People in search of more of a kick continued to manufacture and purchase choc for the next half-century, but once legal options emerged, the alternative beer economy gradually passed away. It eventually became cheaper and easier to just buy a case of Budweiser than to manufacture or buy choc.

The current wave of micro and homebrewing that is sweeping the nation, however, offers an excellent opportunity for a choc revival. If you are brewing beer at home (or work) do me a favor: forget about how smooth or balanced your beer should be, and recall a time when Americans packed their homebrew with tobacco and poison berries. Must everything taste like sunshine and flowers? Shouldn’t there be room for something that makes “an ordinary cottontail rabbit spit in the face of a bulldog”?

Let’s do this thing.

–Ben Nadler

2Natty Light

“Natty” (or “Unnatural Light,” as it’s also called) has long been the unofficial beer of students and the cash-strapped everywhere.

As the market analysts say, Natty “competes on price,” meaning it has little to recommend it beyond being extremely cheap. Depending on where you live, you might be able to pick up a 30-pack for under $15.

Cheap beer is not a fresh idea, but for Natty it wasn’t supposed to be this way. Concocted by Anheuser-Busch in the 1970s, Natty was envisioned as the brewery’s elegant answer to the Miller Lite juggernaut. It wasn’t. Today it’s a punch line even to the people who buy it. And yet, according to Beverage Industry, Natural Light is currently the 5th best-selling beer in the U.S. Natty, it seems, is the beer that America both laughs at and loves. It’s been a strange journey.

Cheap beer is not a fresh idea, but for Natty it wasn’t supposed to be this way. Concocted by Anheuser-Busch in the 1970s, Natty was envisioned as the brewery’s elegant answer to the Miller Lite juggernaut. It wasn’t. Today it’s a punch line even to the people who buy it. And yet, according to Beverage Industry, Natural Light is currently the 5th best-selling beer in the U.S. Natty, it seems, is the beer that America both laughs at and loves. It’s been a strange journey.

The “Father of Light Beer,” according to his Washington Post obituary, was biochemist Joseph L. Owades. Dr. Owades’ specialty was fermentation science, and he first found employment with Rheingold Breweries. A diligent employee, Owades got into the habit of asking non-beer drinkers why they didn’t like beer and he usually got the same answer: They were afraid of getting a beer belly.

This revelation inspired Owades to invent a process to remove the starch from beer, thus reducing carbohydrates and calories. Rheingold liked his idea, and in 1967 introduced Gablinger’s Diet Beer (the “Diet” was later dropped). Cans featured a portrait of a stern-looking man, presumably the mysterious Gablinger, and the riveting slogan “Doesn’t Fill You Up.”

But the world wasn’t ready for diet beer, and Gablinger’s quickly flopped. It was such a disaster that Rheingold had no objection to Dr. Owades sharing his light beer secrets with Meister Brau brewery of Chicago. Meister Brau, a small and struggling brewer with little to lose, decided to take a gamble and rolled out Meister Brau Lite. (Owades claimed that, being from Chicago, the Meister Brau folks didn’t know how to spell the word “light.”)

Meister Brau Lite flopped and took the brewery down with it. The company was sold to Miller, along with the secret of making light beer. At the time, in the 1970s, Miller was only the third-biggest brewery in Milwaukee (behind Pabst Blue Ribbon and Schlitz) and a far cry from Anheuser-Busch, the undisputed market leader in the U.S.

But Miller was determined to make something out of this light beer idea and spend the dollars to market it properly. They would ultimately create one of the longest-running and most memorable advertising campaigns ever mounted.

The crucial task was to persuade male beer drinkers that their new product (to be called Lite Beer from Miller, and later just Miller Lite) was no diet, sissy beer. Their attack was two-pronged. First, hire tough guys and jocks—seemingly every jock on the planet, by the 1980s—to endorse the product. Second, emphasize—loudly and repeatedly—that Lite was “less filling,” so you could drink even more beer thanks to its lightness. “Everything you always wanted in a beer,” the slogan promised. “And less.”

The first television ad, in 1974, featured Super Bowl-winning fullback Matt Snell seated at a table crowded with empty bottles, demonstrating just how un-filling this new light beer really was. Later ads evolved into the famous “tastes great/less filling” shouting matches. By the mid-80s, the TV ads had become elaborate mini-movies featuring dozens of jocks and ex-jocks; plus coaches, referees, sports reporters, Mickey Spillane and Rodney Dangerfield. The ads were genuinely funny and appealing, and sales soared.

Although Dr. Owades would not reap the profits, light beer had finally arrived.

In St. Louis, the Anheuser-Busch honchos were unconcerned by the debut of Miller Lite. August Busch III, fresh off of deposing his own father as head of the brewery in a palace coup, scoffed at the very idea of light beer. “It’s just a matter of time until Miller Lite falls on its face,” he said, according to the book Under the Influence: The Unauthorized Story of the Anheuser-Busch Dynasty.

But when Miller Lite shipped 5 million barrels in its first full year on the market, A-B quickly realized that it had to respond. “We missed the boat,” August III confessed.

But when Miller Lite shipped 5 million barrels in its first full year on the market, A-B quickly realized that it had to respond. “We missed the boat,” August III confessed.

But despite that admission, A-B was still not entirely on board. Their response, when it came, would not be a light version of its flagship brand, Budweiser. Budweiser Light? Bud Light? Unthinkable. That would only serve to damage the prestige of Budweiser, the “King of Beers,” A-B’s brain trust decided. No, instead A-B would launch an entirely new brand: Anheuser-Busch Natural Light, soon shortened to just Natural Light.

Natty was born in 1977, more than two years after Miller Lite. Early print ads claimed it was “brewed with water, rice, hops, barley, and yeast,” whereas Miller Lite, according to the same ad, was brewed with “propylene glycol alginate, amyloglucosidase and potassium metabisulfite.” It weighed in at a mere 97 calories, comparable to Miller Lite’s 96.

Natural Light’s rollout was supported by an expensive TV ad campaign; but where Miller hired mostly athletes, Natty’s pitchmen at first were mostly comedians. Norm Crosby, “The Master of the Malaprop,” appeared in many of the ads. And then there was Ray J. Johnson.

The alter-ego of comedian Bill Saluga, Ray J. Johnson, at the mere mention of the word “name,” launched into a bizarre spiel in a sing-song voice: “You can call me Ray, or you can call me Jay, or you can call me Johnny, or you can call me Sonny… but you doesn’t has to call me Johnson.” The TV ad featured Ray J. spouting his nonsense in a bar, to the exasperation of staff and patrons who just wanted to enjoy their Natural Light in peace.

The ads were a great success — for Saluga, who was rocketed to his 15 minutes of fame. The memory of Ray J. still lingers as a strange and unexplainable relic of the 70s. But Natural Light as a brand made little headway against the Miller Lite advertising juggernaut.

By now it was plain that jocks were the essential ingredient to selling light beer, so A-B took to raiding Miller’s stable of celebrity endorsers. TV ads showed Norm Crosby introducing “athletic supporters” such as Mickey Mantle, Catfish Hunter, and Joe Frazier, all former Miller Lite pitchmen, who now declared that they preferred Natural Light. They all signed a sworn affidavit that they had picked Natural over Miller Lite in a blind taste test.

This talent raid was just one skirmish in a “war,” as August III described it, between A-B and Miller for beer supremacy in the U.S. The war lasted into the late 1980s and was fought on many fronts.

Including the legal. In 1986, Miller tried to halt all sales of Natural Light, arguing to the Federal Trade Commission that its trademark gave it exclusive rights to the words “lite” and “light” in marketing beer. A-B struck back with an FTC complaint of its own, targeting Miller’s then-premium brand, Löwenbräu. Miller brewed Löwenbräu in the U.S. under license from its German creator in Munich; but the American version, A-B argued, did not conform to German beer purity laws, as Löwenbräu ads implied.

Both petitions were dismissed by the FTC, but A-B won the battle anyway—all the negative publicity surrounding Löwenbräu destroyed its reputation, and the Löwenbräu brand, ancient and venerable in Germany, never recovered in the United States.

The legal potshots continued. Miller complained to the FTC again, about the use of the word “natural” in Natural Light ads, and trotted out a team of nutritionists to argue the definition of the word. A-B countered by claiming the advertising slogan for Miller High Life, “the champagne of beers,” was false advertising because beer “contained none of the qualities of champagne.” As before, the FTC rejected both petitions.

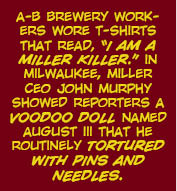

Some of the strategies and weapons deployed in this war would be hard to believe were they not so well-documented in William Knoedelseder’s book Bitter Brew. In St. Louis, A-B brewery workers wore T-shirts that said, “I Am a Miller Killer.” In Milwaukee, Miller CEO John Murphy showed reporters a voodoo doll named August III that he routinely tortured with pins and needles. He also obtained a floor mat emblazoned with the Anheuser-Busch eagle logo, just so he could trample it whenever he sat at his desk.

In the end, Miller need not have bothered with the FTC petitions to stop Natural Light. Natty barely dented Miller’s dominance of the light beer market. Only the eighth-best selling brewery in the U.S. at the start of the 1970s, Miller shot to second place by the end of the decade on the strength of Miller Lite alone. Desperate for success, August III rethought the unthinkable and made the fateful decision to spin off a light version of Budweiser, Bud Light, and throw all the brewery’s considerable advertising resources behind it.

This move was the turning point of the war and the start of Natural Light’s journey into the shadows.

Even in exile, Natty found a niche it could fill. It would be A-B’s entry in the rock-bottom market, their presence on the very lowest tier of the beer shelf, what the market men call the “gladiator pit.” It would get next to no advertising support and have to compete and survive on price alone.

And on that level, Natty has turned into an undeniable success. Freed from the burden of dueling Miller Lite, and now priced in line with its actual worth, Natty turned into a solid seller for A-B. It even proved worthy of a spin-off brand: a malt liquor called Natural Ice that has stuck around since the mid-1990s.

In 2009 came the Great Recession. Beer drinkers began trading down to “sub-premium” brands, and A-B courted them with its first television advertising campaign for Natty since the early years of its launch. There were no celebrities this time around. The crude ads touted “nattyisms”—dull-witted jargon targeting young drinkers and couch-potatoes—but they were good enough to launch Natty into the top five in U.S. beer sales.

Which is where Natty stands today. And that’s a strange thing. Maybe Natty has acquired some of the hipster credibility that somehow turned Pabst Blue Ribbon into an acceptable, even fashionable beer. There are similarities: both are underdog beers that survived in a fierce market without much advertising, and both have short, punchy nicknames (Natty and PBR) that lend them a dash of street cred.

Or maybe cheap beer is just cheap beer, and Natty will fade back into obscurity soon enough. But for now, you can walk into a store and pay not much for a lot of Natty Light without the slightest sense of shame because 1.) your peers are legion, and 2.) long ago, back when it ran with rich jocks and celebs, when all the big shots in the brewing biz called it “The Natural,” Natty Light was a contender.

–Bryan Dent

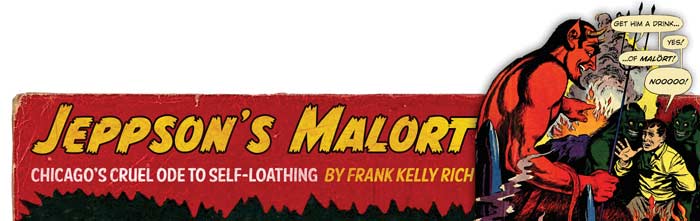

3Jeppson’s Malort

I don’t know how many countries actually signed the Evil Booze Nonproliferation Treaty of 1903, but we can safely say it was a total waste of time because everyone has the fucking bomb.

Every country on this planet makes at least one evil hooch whose main function is punishing outsiders. It’s the drink the locals suggest while trading secret looks and suppressing cruel laughs. A booze so unrelentingly crude, so unmistakably vile that it resists exportation, meaning you’ll rarely get any advance warning. They’re usually sold as digestifs or body tonics, the idea being medicine isn’t supposed to taste good. “Come take your medicine,” is not an entreaty to indulge in a treat. When not busy attacking the dignity of foreigners, these monsters also do domestic duty as challenge-, revenge-, initiation- and rite-of-passage-shots.

Every country on this planet makes at least one evil hooch whose main function is punishing outsiders. It’s the drink the locals suggest while trading secret looks and suppressing cruel laughs. A booze so unrelentingly crude, so unmistakably vile that it resists exportation, meaning you’ll rarely get any advance warning. They’re usually sold as digestifs or body tonics, the idea being medicine isn’t supposed to taste good. “Come take your medicine,” is not an entreaty to indulge in a treat. When not busy attacking the dignity of foreigners, these monsters also do domestic duty as challenge-, revenge-, initiation- and rite-of-passage-shots.

Hungary has Unicum, Serbia has pelinkovac, China has any number of drowned baby rodent/snake liquors, Vietnam has their infamous Three-Lizard liquor, the Czechs have competing slivovitz brands, Ghana has a beer so vile they call it dirt wine. Mexicans have used mezcal to punish gringos for so long that it’s actually becoming a thing in certain masochistic circles. In one of the greatest and most sadistic feats in marketing history, Germany was able to convince an entire planet to flagellate itself until there was a global taste-shift in what was “not entirely disgusting.” Ask a German what he thinks about Jägermeister’s popularity in the U.S., but make sure you have some time on your hands because the cruel laughter will seem to go on forever.

But rarely does a city possess enough inherent meanness to have its own cruel handshake, and it may or may not surprise you to learn that Chicago certainly does.

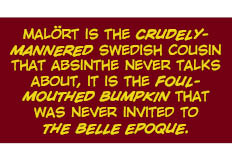

It’s called Jeppson’s Malört. Malört means wormwood in Swedish, and that evil weed is its main gear. Malört is the crudely-mannered Swedish cousin that absinthe never talks about, it is the foul-mouthed bumpkin that was never invited to the Belle Epoch.

“In all the world there is no liquor quite like Jeppson’s,” boasts Jeppson’s website, and I say that’s a good thing.

The Swedes have been choking down a form of malört since medieval times (“for medicinal purposes,” natch), and it snuck into the U.S. with the sporadic waves of Nordic migration.

In his 1907 book The Devil and the Grafter and How They Work Together to Deceive, Swindle and Destroy Mankind, Clifton R. Wooldridge, AKA The Incorruptible Sherlock Holmes of America, makes note that on October 6th 1906, Chicago police raided and shut down a business on Divisions Street calling itself the “Honduras National Lottery.” One Carl Jeppson, a Swedish immigrant, was arrested and fined $50 by Justice John R. Caverly.

Was this the same Carl Jeppson that rolled out Jeppson’s Malört a decade or so later? Almost certainly. According to the 1910, 1920, and 1930 U.S. Censuses, there was only one Carl Jeppson living in Chicago, or Illinois for that matter.

No telling what Carl got up to after that inconvenient raid, but eventually he decided to gamble on something of which he had a firmer understanding (than Central American lotteries). He reached back to his pre-migrant days, back to the frozen potato fields of Uppsala, and for some sadistic reason we may never fully understand, came up with the most awful thing he could remember: malört.

Maybe the rank humiliation of being dragged out of his thriving Honduran Lottery office in handcuffs, then having to endure all that condescending bullshit Justice Caverly surely would have laid on him at the court appearance warped his mind and filled his heart with an insatiable ache for revenge. Maybe he held close to this heart that fine old Viking proverb that roughly translates to: “Make your enemies wonder when you’ll attack, then hit the bastards the day before.”

Which isn’t an easy thing to do, when you think about it, so Carl probably just figured: “What the hell, I’ll just hit them with the malört. Once they get a taste of that awful stuff, they won’t even think of fucking with my lottery business again.”

Carl was under no illusion as to what he was selling. He went around saying things like, “My Malört is produced for that unique group of drinkers who disdain light flavor or neutral spirits.” Indeed. Or anyone who disdains decency and good taste, for that matter.

Carl enjoyed a small amount of success with his new brew. To some homesick Swedish immigrants it tasted like the Old Country (and no doubt to others it tasted like why they left the Old Country.) There’s nothing like a shot of malört to bring back that unique feeling of trying to coax crops from frozen tundra then having to live on boiled reindeer hooves for the rest of the goddamn year.

Jeppson’s is the kind of hideous weed that grows best in harsh environs, so it should surprise no one that the business didn’t truly take root and bloom until the black shadow of National Prohibition fell across the land. This was a time when people were so desperate they’d drink actual poison in hopes of getting tight, so Jeppson’s probably didn’t seem all that bad. Say what you want about malört, but it doesn’t kill you outright. It just makes you wish you were dead.

This was a time when every drink came affixed with public shame and personal guilt, so naturally Jeppson’s came into its own, able as it was to provide the sin and penance in a single convenient package. Why wait for the chastising whipsong of a hangover when you can suffer the lash with every sip?

When Prohibition ended in 1933, Jeppson very wisely sold his recipe to liquor distributor George Brode. When Brode decided to leave the booze business for the legal profession, he sold off his entire stable of liquors—except Jeppson’s Malört, which he kept around as a sort of kinky hobby.

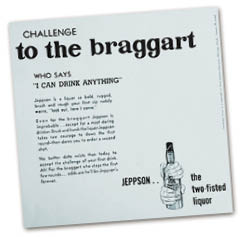

For the next half century, Brode tried mightily to inflict Jeppson’s on as many unsuspecting Americans as possible, with little effect. Christening it “The Two-Fisted Liquor,” Brode’s print advertising campaigns relied almost entirely on straight-from-the-shoulder shots at the drinker’s masculinity and courage.

Challenge to the braggart who says “I can drink anything,” snarls the lead of one print ad. Only a horse’s tail would switch from Jeppson’s, warns another.

Challenge to the braggart who says “I can drink anything,” snarls the lead of one print ad. Only a horse’s tail would switch from Jeppson’s, warns another.

Brode’s legal secretary, Patricia Gabelick, took the reins when Brode passed away in 1999, but the retro-style campaign continues to this day. There is something very fine and nostalgic about it—in these days of slick innuendo and carefully-vetted PC language, Jeppson’s sticks to the brand of straight talk you’d have heard during a gathering of men and broads, circa 1950.

Perhaps precisely for that reason, Jeppson’s popularity has been on the upswing lately. Bartenders and hipsters swear by it, there’s a short documentary, at least one rousing anthem (“The Malört Song,” by Archie Powell and the Exports), and sales are shooting through the roof.

It’s become so popular, in fact, that three micro-distillers (who are evidently not all the pioneering paladins the media makes them out to be) took a crack at ripping off Jeppson’s style and substance. Just when a little blood had started to pulse in Jeppson’s withered veins, FEW Spirits, Letherbee Distillers (both from Chicago) and Bittermens (Louisiana) all decided to “pay homage” by jumping onto Jeppson’s neck like a gang of vampires and releasing similar products. Fortunately, Jeppson’s lawyer was able to lash the fuckers off the company’s back with a series of brutal legal actions, and the trio backed away, hissing, into the shadows from whence they came.

Up until three months ago, I possessed only a nebulous understanding of Jeppson’s. I’d picked up vague vibrations over the years, Chicago-accented voices using what must have been regional profanity, overheard snatches of conversation about some evil thing called malört, a word that just seemed a little too on the nose for something sinister.

Then a local bar owner, formerly of Chicago, explained what it was and essentially threw down the Windy City version of that infuriating British gauntlet: “Come have a go if you think you’re hard enough.”

I couldn’t find a Denver liquor store so disreputable that they’d stock it, so I ordered it online. It arrived four days later, and I immediately gave it a go because I am definitely hard enough.

If you drink a lot of high-proof Czech absinthe, as I do, you won’t be taken unawares. My first reaction? Low-grade absinthe evenly cut with ditch water. Which, in a sense, makes it a harder shot than straight absinthe because you don’t get that refreshing, taste-bud-numbing bite that 130+ proof absinthe provides. It tastes less pure, more sinister, more malörty.

Which lends it a unique niche to fill. I keep a bottle around for special occasions: unwanted guests, garrulous friends, and those dire times when I need to remind myself, Things could be worse. Shoot this and tell me I’m wrong.

–Frank Kelly Rich

4Salamander Brandy

Slovenia is an oft-overlooked nation of two million people in central Europe. Among its contributions to humanity are dazzling architecture, fine pastries, and a drink known as salamander brandy.

Throw some of those icky creatures into a pot of fermented fruit and they’ll fight so desperately for their slithering lives that they’ll secrete every drop of their toxic mucous (defense mechanism) until they die. These secretions (and their mind-warping neurotoxins) comprise the magic ingredient of a brandy that is perhaps the most potent and unpredictable aphrodisiac in all of human history.

By “aphrodisiac” I’m not talking about a lousy candle and a few milligrams of Viagra. Drinkers of salamander brandy can become so stimulated that they no longer discriminate between age, gender, species, or even between animate and inanimate objects. Your neighbor’s backyard table might take the shape of a giggling, prostrated Taylor Swift.

By “aphrodisiac” I’m not talking about a lousy candle and a few milligrams of Viagra. Drinkers of salamander brandy can become so stimulated that they no longer discriminate between age, gender, species, or even between animate and inanimate objects. Your neighbor’s backyard table might take the shape of a giggling, prostrated Taylor Swift.

Even if you’re a hardened substance abuser, you might want to self-isolate before popping your salamander-brandy cherry, lest you find yourself facing down a mob of disgusted cops clubbing you off some yuppie’s Schnauzer.

According to the British website grailtrail.co.uk[1], there should be only one mucous-secreting salamander per every five liters of brandy. This stuff is powerful—and toxic. Do not start rounding up random salamanders so you can suck off their mucous. It well might be your last endeavor.

Take your time with this drink. Even after the condemned salamander have oozed all over your liters of fermented fruit, it is advisable to add some wormwood, and then allow the concoction to age for several weeks prior to any consumption.

Most drinkers haven’t heard of this brew, which is probably for the best. However, there is some existing info. The most prominent modern literature on salamander brandy was an article in a 1995 edition of the Slovenian magazine Mladina (written in the Slovene language).

The following year, one Ivan Valenčič wrote the article, “Salamander Brandy: A Psychedelic Drink Made in Slovenia,” for the Yearbook for Ethnomedicine and the Study of Consciousness. Thankfully, this salamander contribution is available in English.

Valenčič tells how salamander brandy drinkers might experience such visual hallucinations as “colorful flashes.” Auditory hallucinations are also a possibility. More titillating is the mention of “sexual disorientation,” in which a drinker whose normal amorous pursuits were of the “commonest banality” is cast suddenly into a world where any perceivable object is infused with a mammoth charge of eroticism.

In addition to the concupiscent impact, drinkers have been known to experience a sense of time distortion. And some scrupulous types might be stricken with “spiritually negative emanation,” owing to how the salamander(s) was cruelly murdered in order to create the brandy (and its psychoactive effects).

The availability, production and history of this drink have been a rather secret affair. Some say it dates all the way back to the Middle Ages. For several ensuing centuries, the territory of current-day Slovenia was a witch-hunting hotbed, where people were accused, convicted and burned as “witches” because of eccentric behavior. Under such circumstances, consuming a sexually-charged psychedelic would’ve been especially perilous. Evidently, some thought it worth the risk.

Even now, with witch hunts a distant memory, the drink is an underground item. The Slovenian Tourist Board says, “Salamander brandy is prohibited because it causes hallucination and is not sold in shops.”

The Slovenian Embassy in Washington DC put your humble correspondent in touch with their Economic Counselor, who said that salamander brandy is “not consumed commonly in any part of Slovenia.”

So if you’re trying to find this brandy in its homeland, you will need an underground contact.

Or you can skip the Slovenian getaway, and make your own brew.

[1] Now defunct.

–Ray Cavanaugh