I don’t know how many countries actually signed the Evil Booze Nonproliferation Treaty of 1903, but we can safely say it was a total waste of time because everyone has the fucking bomb.

Every country on this planet makes at least one evil hooch whose main function is punishing outsiders. It’s the drink the locals suggest while trading secret looks and suppressing cruel laughs. A booze so unrelentingly crude, so unmistakably vile that it resists exportation, meaning you’ll rarely get any advance warning. They’re usually sold as digestifs or body tonics, the idea being medicine isn’t supposed to taste good. “Come take your medicine,” is not an entreaty to indulge in a treat. When not busy attacking the dignity of foreigners, these monsters also do domestic duty as challenge-, revenge-, initiation- and rite-of-passage-shots.

Hungary has Unicum, Serbia has pelinkovac, China has any number of drowned baby rodent/snake liquors, Vietnam has their infamous Three-Lizard liquor, the Czechs have competing slivovitz brands, Ghana has a beer so vile they call it dirt wine. Mexicans have used mezcal to punish gringos for so long that it’s actually becoming a thing in certain masochistic circles. In one of the greatest and most sadistic feats in marketing history, Germany was able to convince an entire planet to flagellate itself until there was a global taste-shift in what was “not entirely disgusting.” Ask a German what he thinks about Jägermeister’s popularity in the U.S., but make sure you have some time on your hands because the cruel laughter will seem to go on forever.

But rarely does a city possess enough inherent meanness to have its own cruel handshake, and it may or may not surprise you to learn that Chicago certainly does.

Malört is the crudely-mannered Swedish cousin that absinthe never talks about, it is the foul-mouthed bumpkin that was never invited to the Belle Époque.

It’s called Jeppson’s Malört. Malört means wormwood in Swedish, and that evil weed is its main gear. Malört is the crudely-mannered Swedish cousin that absinthe never talks about, it is the foul-mouthed bumpkin that was never invited to the Belle Époque.

“In all the world there is no liquor quite like Jeppson’s,” boasts Jeppson’s website, and I say that’s a good thing.

The Swedes have been choking down a form of malört since medieval times (“for medicinal purposes,” natch), and it snuck into the U.S. with the sporadic waves of Nordic migration.

In his 1907 book The Devil and the Grafter and How They Work Together to Deceive, Swindle and Destroy Mankind, Clifton R. Wooldridge, AKA The Incorruptible Sherlock Holmes of America, makes note that on October 6th, 1906, Chicago police raided and shut down a business on Divisions Street calling itself the “Honduras National Lottery.” One Carl Jeppson, a Swedish immigrant, was arrested and fined $50 by Justice John R. Caverly.

Was this the same Carl Jeppson who rolled out Jeppson’s Malört a decade or so later? Almost certainly. According to the 1910, 1920, and 1930 U.S. Censuses, there was only one Carl Jeppson living in Chicago, or Illinois for that matter.

No telling what Carl got up to after that inconvenient raid, but eventually he decided to gamble on something of which he had a firmer understanding (than Central American lotteries). He reached back to his pre-migrant days, back to the frozen potato fields of Uppsala, and for some sadistic reason we may never fully understand, came up with the most awful thing he could remember: malört.

Maybe the rank humiliation of being dragged out of his thriving Honduran Lottery office in handcuffs, then having to endure all that condescending bullshit Justice Caverly surely would have laid on him at the court appearance warped his mind and filled his heart with an insatiable ache for revenge. Maybe he held close to this heart that fine old Viking proverb that roughly translates to: “Make your enemies wonder when you’ll attack, then hit the bastards the day before.”

Which isn’t an easy thing to do, when you think about it, so Carl probably just figured: “What the hell, I’ll just hit them with the malört. Once they get a taste of that awful stuff, they won’t even think of fucking with my lottery business again.”

Carl was under no illusion as to what he was selling. He went around saying things like, “My Malört is produced for that unique group of drinkers who disdain light flavor or neutral spirits.” Indeed. Or anyone who disdains decency and good taste, for that matter.

Carl enjoyed a small amount of success with his new brew. To some homesick Swedish immigrants it tasted like the Old Country (and no doubt to others it tasted like why they left the Old Country.) There’s nothing like a shot of malört to bring back that unique feeling of trying to coax crops from frozen tundra then having to live on boiled reindeer hooves for the rest of the goddamn year.

Jeppson’s is the kind of hideous weed that grows best in harsh environs, so it should surprise no one that the business didn’t truly take root and bloom until the black shadow of National Prohibition fell across the land. This was a time when people were so desperate they’d drink actual poison in hopes of getting tight, so Jeppson’s probably didn’t seem all that bad. Say what you want about malört, but it doesn’t kill you outright. It just makes you wish you were dead.

This was a time when every drink came affixed with public shame and personal guilt, so naturally Jeppson’s came into its own, able as it was to provide the sin and penance in a single convenient package. Why wait for the chastising whipsong of a hangover when you can suffer the lash with every sip?

When Prohibition ended in 1933, Jeppson very wisely sold his recipe to liquor distributor George Brode. When Brode decided to leave the booze business for the legal profession, he sold off his entire stable of liquors—except Jeppson’s Malört, which he kept around as a sort of kinky hobby.

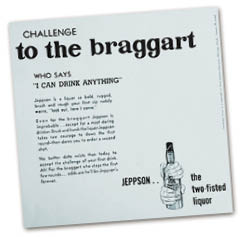

For the next half century, Brode tried mightily to inflict Jeppson’s on as many unsuspecting Americans as possible, with little effect. Christening it “The Two-Fisted Liquor,” Brode’s print advertising campaigns relied almost entirely on straight-from-the-shoulder shots at the drinker’s masculinity and courage.

For the next half century, Brode tried mightily to inflict Jeppson’s on as many unsuspecting Americans as possible, with little effect. Christening it “The Two-Fisted Liquor,” Brode’s print advertising campaigns relied almost entirely on straight-from-the-shoulder shots at the drinker’s masculinity and courage.

Challenge to the braggart who says “I can drink anything,” snarls the lead of one print ad. Only a horse’s tail would switch from Jeppson’s, warns another.

Brode’s legal secretary, Patricia Gabelick, took the reins when Brode passed away in 1999, but the retro-style campaign continues to this day. There is something very fine and nostalgic about it—in these days of slick innuendo and carefully-vetted PC language, Jeppson’s sticks to the brand of straight talk you’d have heard during a gathering of men and broads, circa 1950.

Perhaps precisely for that reason, Jeppson’s popularity has been on the upswing lately. Bartenders and hipsters swear by it, there’s a short documentary, at least one rousing anthem (“The Malört Song,” by Archie Powell and the Exports), and sales are shooting through the roof.

It’s become so popular, in fact, that three micro-distillers (who are evidently not all the pioneering paladins the media makes them out to be) took a crack at ripping off Jeppson’s style and substance. Just when a little blood had started to pulse in Jeppson’s withered veins, FEW Spirits, Letherbee Distillers (both from Chicago) and Bittermens (Louisiana) all decided to “pay homage” by jumping onto Jeppson’s neck like a gang of vampires and releasing similar products. Fortunately, Jeppson’s lawyer was able to lash the fuckers off the company’s back with a series of brutal legal actions, and the trio backed away, hissing, into the shadows from whence they came.

Up until three months ago, I possessed only a nebulous understanding of Jeppson’s. I’d picked up vague vibrations over the years: Chicago-accented voices using what must have been regional profanity, overheard snatches of conversation about some evil thing called malört, a word that just seemed a little too on the nose for something sinister.

Then a local bar owner, formerly of Chicago, explained what it was and essentially threw down the Windy City version of that infuriating British gauntlet: “Come have a go if you think you’re hard enough.”

I couldn’t find a Denver liquor store so disreputable that they’d stock it, so I ordered it online. It arrived four days later, and I immediately gave it a go because I am definitely hard enough.

If you drink a lot of high-proof Czech absinthe, as I do, you won’t be taken unawares. My first reaction? Low-grade absinthe evenly cut with ditch water. Which, in a sense, makes it a harder shot than straight absinthe because you don’t get that refreshing, taste-bud-numbing bite that 130+ proof absinthe provides. It tastes less pure, more sinister, more malörty.

Which lends it a unique niche to fill. I keep a bottle around for special occasions: unwanted guests, garrulous friends, and those dire times when I need to remind myself: Things could be worse. Shoot this and tell me I’m wrong.