For Whom the Booze Tolls

It was a local blacksmith who introduced a young Ernest Hemingway to the world of drinking, giving him a glass of hard cider. From that humble introduction Hemingway went forth to engage the wide world of alcohol. Like nearly all the great drunks, Hemingway was a wide-ranging omnivore when it came to the booze. While a young man in Europe he absorbed enough wine, cognac, brandy, grappa and absinthe to start thinking himself something of an expert. He didn’t consider a meal a meal unless wine was served and sometimes that meant six bottles. Glassware be damned, he was not above drinking straight from the bottle—he compared it to “a girl going swimming without her swimming suit.”

On safari he claimed he was never inebriated, though his hunting companions testified his first drink arrived with the dawn and that around the camp “his drinking would have killed a less tough man.”

While covering WWII from the front lines, he kept his canteen filled with gin and personally liberated (with the help of his private army) the Cambon Bar of Paris’ Ritz Hotel.

In Cuba Hem cranked up his game. On a typical evening he “Started out with absinthe, drank a bottle of good red wine with dinner, shifted to vodka in town then battened it down with whiskeys and sodas until 3am.” Although Hemingway was fond of telling visiting interviewers that he rose at 4:30am and never drank before noon, a journalist who actually observed him in action at his Cuban home reported that upon rising Hemingway “usually starts drinking right away and writes standing up, with a pencil in one hand and a drink in the other.”

“I suppose he was drunk the whole time but seldom showed it,” friend Denis Zaphiro said. “Just became merrier, more lovable, more bull-shitty. Without drink he was morose, silent and depressed.”

True Story: Contrary to popular myth, it was not the booze that drove Hemingway to shoot himself. He pulled the trigger after three months of forced abstinence. In lieu of alcohol, he was force-fed a steady diet of shock treatments and promises he would never be allowed to drink again. Hem’s son wrote, “He might have survived with alcohol, but could not live when deprived of it.”

Imagine Whiskey Is the Fire

Weened on beer as a child, this gangly southern belle graduated to drinking straight gin from water glasses before she left high school.

The stellar success of her first novel The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter convinced Carson to move to the literary capitol of New York. Attending a ferocious flurry of cocktail parties thrown in her honor, she took no small amount of pleasure in shocking the gathered intelligentsia — not with boorish behavior (she was generally quite shy), but by showing them how much booze a young lady from the South could put away. Carson possessed a prodigious capacity for liquor and reveled in sending large proud Yankees staggering home while she drank deeper into the night.

Carson liked sherry with her tea, brandy with her coffee and her purse with a large flask of whiskey. Between books, when she was neither famous nor monied, she claimed she existed almost exclusively on gin, cigarettes and desperation for weeks at a time. During her most productive years she employed a round-the-clock drinking system: she’d start the day at her typewriter with a ritual glass of beer, a way of saying it was time to work, then steadily sip sherry as she typed. If it was cold and there was no wood for the stove, she’d turn up the heat with double shots of whiskey. She concluded her workday before dinner, which she primed with a martini. Then it was off to the parties, which meant more martinis, cognac and oftentimes corn whiskey. Finally, she ended the day as it began, with a bedtime beer.

Her recuperative abilities are the stuff of legend — she would rise the following morning, shake off her hangover like so much dust, down her morning beer and get back to work.

True Story: Carson answered critics of her lush lifestyle in her novella The Ballad of the Sad Cafe: “It is known that if a message is written with lemon juice on a clean sheet of paper there will be no sign of it. But if the paper is held for a moment to the fire then the letters turn brown and the meaning becomes clear. Imagine that the whiskey is the fire and the message is which is known only in the soul of a man.”

Blood of the Gods

“The ultimate glory is to get drunk and drunker,” Bukowski wrote and he wasn’t terribly particular how he attained that greater glory. His broad tastes were revealed in his ode to his IBM Selectric typewriter into which, over the years, he’d spilled “beer, wine, whiskey, vodka, ale” and cigar ash. Bukowski wasn’t the least bit prejudiced — all were welcome, so long as they were cheap.

Whenever Buk managed to claw a paycheck from the Man, he’d stock up, laying in jugs of cheap wine which he positioned in a semi-circle around his bed as totems against the cruel world lurking outside. “So I stayed in bed and drank,” he wrote. “When you drank the world was still out there, but for the moment it didn’t have you by the throat.”

In the bars he leaned to cheap drafts and well liquor, for as he wisely noted, “Liquor is like a symphony . . . you don’t use it as a downer, you use it to leap up into the sky when you have pain.”

Like many drunks, his taste in booze shifted with his age and tax bracket. He drank Schlitz and rotgut when he was poor and undiscovered then traded up to good German wine, quality whiskey and the occasional Heineken when fat royalty checks finally found his mailbox. “The blood of the gods,” he said of wine. “You can drink a lot of it and stay relatively sane. I used to drink an awful lot of beer. But wine is the best for creation. You can write three or four hours.”

Drinking beer “was like breathing,” a man without wine was a “bird without wings,” and whiskey, well, whiskey made him misanthropic.

Largely a solitary drinker, Buk abhorred the party circuit, saying, “My theory is if you mix enough people together you don’t get soup or salad, you get shit. That’s the sign of a good whiskey drinker anyway, drinking it by yourself shows a proper reverence for it.”

True Story: Diagnosed with a bleeding ulcer, Bukowski was told by doctors he would die if he took another drink. The news shook Buk so badly he ducked into the nearest bar and sank a couple beers to steady his nerves. He managed not to die (while drinking prodigiously) for another 40 years.

Bubbly and the Bulldog

While the hero of the Blitz was in temperament (and perhaps in appearance) the very embodiment of a British bulldog, Winston Churchill had Continental tastes when it came to drinking.

“I drink champagne at all meals, and buckets of claret and soda in between,” he was not ashamed of saying. He also noted that “Hot baths, cold champagne, new peas and old brandy” were the four essentials of life. During the ferocious struggle with the Nazis, a royal visitor reported that Winston was putting away enough champagne to “undermine the health of any ordinary man.”

Fortunately for the free world, Churchill was no ordinary man.

Not to say he ignored the British Empire’s offerings. He kept his mind primed with Scotch and sodas during the long workday and relaxed after hours with his now famous Churchill martini: a glass of chilled English gin flavored with a solemn nod toward occupied France in lieu of vermouth, which was naturally difficult to get.

“There is always some alcohol in his bloodstream,” biographer William Manchester attested, “and it reaches its peak late in the evening after he has had two or three Scotches, several glasses of Champagne, at least two brandies, and a highball.” To put a finer point to it, Churchill’s favorite brandy was Hine, his preferred Champagne Pol Roger, and his top Scotch Johnnie Walker Red Label.

True Story: While visiting King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia, Winston was informed he could neither smoke nor drink, for religious reasons, during a banquet thrown in his honor. Winston wasn’t having any. He informed the monarch that, “My religion prescribed as an absolute sacred ritual smoking cigars and drinking alcohol before, after and if need be during all meals and the intervals between them.”

Southern Born Swiller

When asked if he drank while he wrote, Faulkner coyly replied, “Not always.” When asked to name the tools he needed for his trade, he listed, “paper, tobacco, food, and a little whiskey.” Of course, his idea of what qualified as “a little whiskey” was entirely relative.

The scion of a long distinguished line of drunkards, Faulkner began his drinking career sipping moonshine at the precocious age of seven. While attending Ol’ Miss, the poor but resourceful student managed to ease down a quart of bourbon a day. It helped him to concentrate on his studies, he informed classmates. Later in life Faulkner would self-prescribe bourbon as a sure cure for a great many ailments, including sore throat, bad back, shyness and “general malaise.”

Proud son of the South that he was, Faulkner preferred bourbon, particularly Old Crow, but was willing to compromise: “Between scotch and nothing,” he famously remarked, “I’ll take scotch.” During Prohibition, of course, there existed a very liberal idea as what passed for scotch: in his neck of the woods it usually meant raw white liquor (local or Cuban) flavored with creosote, an oily distillate of wood or coal tar.

The fare wasn’t much better when he moved to New York as a young man — in his letters home he decried the low quality bathtub gin and complained that all the bootleggers were swindlers, as opposed to the upstanding moonshiners of Mississippi.

True Story: He always spoke highly of corn liquor, what he called “white mule,” and claimed to have drank it by the gallon, sometimes at the expense of his dietary habits. “There is a lot of nourishment in an acre of corn,” he noted, especially when distilled into liquid form.

The Three Million Dollar Man

W.C. Fields swore he never imbibed while sleeping and drank nothing stronger than gin before breakfast. A man’s got to know his limitations.

On the set, Fields kept a vacuum flask of gin martinis close at hand (he referred to it as “double-strength lemonade”) but reassured his concerned wife in a letter that despite what the media claimed, he seldom took a drink on the set before 9 am.

Before breakfast and while on the set Fields may have stuck to gin, but the rest of the day was devoted to whiskey. Born above a bar and no stranger to poverty as a child (he had to make due with cheap jug wine), he became a something of a hoarder as an adult. When he saw the winds of Prohibition blowing in, he loaded his basement and attic with literally thousands of bottles of whiskey and gin.

After Prohibition was finally repealed, Harpo Marx was astonished to find hundreds of cases of liquor stacked in Field’s attic. “Bill,” he exclaimed, “what’s with all the booze?” Explained Fields: “Never can be sure Prohibition won’t come back, my boy!”

Averaging two quarts of liquor a day, in 1947 Fields informed Newsweek that, “In my lifetime, I imagine, I have consumed at least $200,000 worth of whiskey.” In modern dollars that’s well over $3,000,000. His favorite quart? I.W. Harper Kentucky Straight Bourbon.

True Story: Hours after the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor, Fields wheeled a hand truck to the nearest liquor store and loaded it up with six cases of gin. On his way home he ran into a friend who was curious as to why he needed 72 bottles of liquor. Fields answered, “I think it’s going to be a short war.”

In Like Him

“I’ve had a hellava lot of fun,” Errol Flynn said. “And I loved it, every minute of it.”

Acting was always a side gig for Flynn. He certainly didn’t mind the scads of money he made jumping around in tights in front of a camera but what he really liked to do was run amok on a global scale.

Flynn (Baron to his drinking buddies) lived a truly adventurous life. Prior to finding fame as an actor, Flynn worked as a policeman, soldier, fisherman, sailor, treasure hunter and mining speculator. Scandals followed the dashing scoundrel right up to the day he died, but he never seemed to mind. Privately, he relished his unsavory reputation and found great pleasure in shocking the public’s sensibilities.

“I like my whisky old and my women young,” Flynn often repeated, but when the latter half of that quote got him in dutch with the law, it was not five shots of whisky he downed before taking the stand and beating the charges. It was vodka. Off the clock he preferred the brown liquors (Johnnie Walker was a favorite) but while on the job he preferred the “no-tell” nature of the Russian spirit. Each morning before heading off to work, Flynn loaded a leather doctor’s bag with his “daily medicine” — two fifths of vodka. When he was ultimately banned from drinking on the set, he took his subterfuge one step further—he injected oranges with vodka and devoured them with impunity between takes.

True Story: When their drinking buddy John Barrymore died, Errol Flynn and director Raoul Walsh holed up in a Hollywood bar, wishing they could share one last drink with their old friend. Overcome with grief, Walsh excused himself while Flynn continued drinking. Finally staggering home at 4am, Flynn walked in his front door, flicked on the lights, and who should be reclined in an armchair with drink in hand? His old, dead buddy John Barrymore. Walsh and two compatriots had spirited Barrymore from the funeral parlor for one last farewell round with his chums.

Defender of the Faith

Alcohol’s most eloquent, stalwart and untiring defender during the dark days of Prohibition was undoubtedly author, critic and editor H.L. Mencken. On the pages of the Baltimore Sun, for all the world to see, Mencken used his rapier wit to expertly shred the Dry gang’s scurrilous arguments.

He viewed the national ban on booze as nothing less than an assault on basic American liberties, had not the faintest intention of obeying it and was willing to say so in print, declaring, “I drink exactly as much as I want, and one drink more.”

Upending standard Prohibitionist doctrine, Mencken asserted it was the Drys, not the drunkards, who were the real savages. “Pithecanthropus erectus was a teetotaler,” he pointed out, “but the angels, you may be sure, know what is proper at 5 pm.”

Mencken wasn’t the sort to turn down a drink, whether it be wine, gin, grappa or whiskey. “I’m ombibulous,” he confessed. “I drink every known alcoholic drink and enjoy them all.” He reckoned that the cocktail qualified as “the greatest of all contributions of the American way of life to the salvation of humanity.”

But what he truly loved was beer. While he was willing and able to drink the bootleg varieties, Mencken received a steady stream of the good stuff by arranging to have cases of European brew hidden in the huge rolls of newsprint shipped to the Sun from Canadian paper mills.

The king of beers, as far as H.L. was concerned, was Czech Pilsner. Such was his devotion that he embarked on a pilgrimage to Pilsen, Czechoslovakia “the home of the best beer on earth and hence one of the great shrines of the human race.”

Every guest in Mencken’s home, which he called “the best bar in Baltimore,” received a beer served in one of the 267 steins he kept on hand.

True Story: Mencken traded the movie rights to his essay “History of the Bathtub” for a monthly shipment of two cases of Canadian ale for the rest of his life.

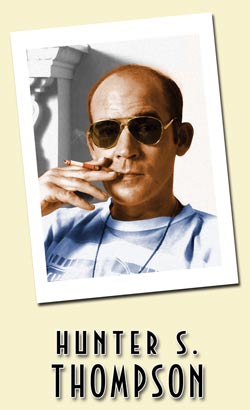

Sleep Late, Get Wild, Drink Whiskey

Like most true acolytes of alcohol, Hunter S. Thompson loved booze in all its many forms. He had his mainstays, to be sure, but on any given occasion he could be found drinking beer, wine, tequila, rum, gin, liqueurs, Margaritas, Bloody Marys, Daiquiris — anything. So long as it had booze in it, there wasn’t a beverage he wasn’t willing to spill into his bloodstream.

During his tenure in Puerto Rico as a reporter for El Sportivo, he feasted on the local rums; later, while covering presidential campaigns, he’d routinely shock the more traditional journalists by starting the day with a six-pack of Heineken and a bottle of gin.

It was whiskey, however, that was his lifelong love. As a young man his call was Old Crow, but as he matured he fell under the trance of Chivas Regal Scotch and Wild Turkey Bourbon. He preferred Chivas when driving or relaxing (he called Chivas on the rocks his “snow cone”) and Turkey when it was time to crank up the fun or turn out pages.

Like many of us, he used a progressive system: he’d start the day with beer and cocktails, then slide into straight liquor. He made a habit of ordering three to six drinks at a time—he had little patience for the vagaries of the wait staff, he wanted what he wanted and he wanted it right now.

He once described himself as “a lazy drunken hillbilly with a heart full of hate who has found a way to live out where the real winds blow—to sleep late, have fun, get wild, drink whiskey, and drive fast on empty streets with nothing in mind except falling in love and not getting arrested.”

True Story: Hunter hit his stride early. At his first meeting with his New York publishers, they watched in amazement as young Hunter poured down 20 double Wild Turkeys in three hours (on their tab, of course), then walk out as if he’d been sipping tea.

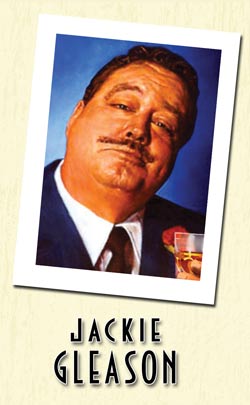

The Great Drunk

Like many rough-and-tumble kids who came of age during Prohibition, Jackie Gleason, at the tender age of 12, cut his teeth on bootleg gin.

Once he’d made his scratch, however, he immediately switched to Scotch. “Some drink to forget, some drink to remember—me, I drink to get bagged,” he confessed, and Scotch, usually J&B, was his preferred method of getting into said bag. He occasionally took it neat or with soda, but generally preferred it on the rocks.

Not to say the Great One never strayed from his Highland mistress; he prided himself on his gin martinis, went through a serious vodka phase (“It’s beautiful, pal—no hangovers”), drank bourbon by the case and was known to rehydrate, come morning, with pitchers of beer.

But it was Scotch he sipped from a tea cup—on camera—during The Jackie Gleason Show. He laid down at least fifth a day and when asked why he needed so much, and so often, he quipped: “I don’t drink to get rid of my warts, I drink to get rid of yours.”

Jackie was not above using his celebrity to get his hands on free booze: he made a point of mentioning his favorite brands on the air, knowing the distilleries would ship him at least a case as a thank you.

True Story: Jackie and President Richard Nixon once met for a scotch-fueled bull session and at the end of the evening Gleason swore he could barely stagger from the room while Nixon walked out “as straight as a soldier.”

Which suggests that either Nixon was a helluva boozer (considering Jackie’s capacity) or, as Hunter S. Thompson often claimed, was in league with the Devil.

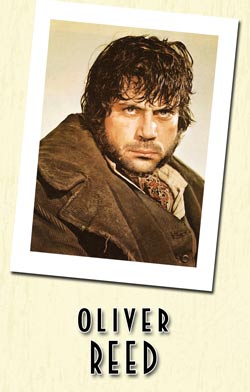

The Werewolf of London

“I do not live in the world of sobriety,” Oliver (Ollie if he was drunk) Reed pointedly said and he wasn’t making an idle boast. While many of the great drunks in this collection took great pride in appearing sober no matter how much they poured down, Oliver reveled in the behavior-enhancing aspect of drink. He would start a spree in the guise of a kind and courtly gentleman then, as the night (or day) progressed, he would transform, werewolf-like, into a wild beast utterly unburdened by society’s rules of conduct. He wouldn’t tolerate pretension or slacking off while in that exalted state — yawn or refuse a drink in his presence and he was likely to hurl you down the nearest flight of stairs.

He also employed alcohol as a tool: he claimed he couldn’t have done the nude wrestling scene with Alan Bates in the film Women in Love without the aid of a bottle of vodka, and when he had to lose weight for a role he went a strict vodka-only diet.

Oliver wasn’t noted for any glaring prejudices when it came to alcohol or women, though he generally preferred English beer, Irish whiskey, dark rum and well-built blondes.

A large powerful man, Oliver bulled his way through life without the weight of remorse or regrets. Except one. “My only regret,” he confessed, “is that I didn’t drink every pub dry and sleep with every woman on the planet.”

No one can say he didn’t try — his sexual exploits were legendary and on one occasion he sank an astonishing 106 pints of beer without break.

True Story: Oliver leapt from this mortal coil in a Maltese pub (now named in his honor) after vanquishing eight bottles of German beer, three bottles of Captain Morgan’s rum and sundry double Famous Grouse whiskies. After adding a final, farewell whisky to his $866 tab, he promptly died of a heart attack.

Just a Little One

As a young woman, author and critic Dorothy Parker despised the taste of liquor. Upon discovering she preferred the company of hard-drinking men, however, she adapted. And how.

“Just a little one,” she’d tell speakeasy companions, unironically at first. She first courted the most readily available suitor, bootleg gin, usually in the form of a dry Martini. She came to like Martinis so much she took to drinking them from noon to night “as if she were having ice tea on a hot day.” She didn’t mind wine, thought champagne rather fine, but couldn’t tolerate beer.

Like so many of her relationships, her romance with gin would not end well — later in life she developed a powerful loathing for the liquor.

Lesser suitors had to stand aside once Parker met Scotch. It quickly became Dottie’s steady beau; she might flirt with other liquors at parties, but it was Scotch she took home. She preferred Haig and Haig neat when she could afford it (bootleggers charged $12 a bottle, an outrageous sum at the time), but would settle for the locally produced rotgut in a pinch. This ersatz “Scotch” was so rotten she once mistook a real case of appendicitis for the usual after-effects of putting away a bottle the night before. Her hangovers, which she termed “the rams,” were so magnificent she declared they “ought to be kept in the Smithsonian under glass.”

Suffering from a lifelong bout of depression, Parker sporadically entertained the idea of committing suicide but managed to drink enough to keep the urge at bay and live to the respectable age of 73.

True Story: Three sheets to the wind, Parker and fellow writer Robert Benchley exited a Manhattan speakeasy to behold a procession of elephants trundling down the street (they weren’t pink — the circus was in town.) Benchley announced it was time to go on the wagon, but Parker convinced him it was a better idea to return to the speakeasy for another drink.