The alcohol industry is forever foisting new “sensations” on the drinking public.

They come and go. Designer vodkas flash and fade like hastily assembled boy bands; new beer genres wail for attention then spiral silently down the drain; strange liqueurs try to muscle their way into our shot glasses then scurry back to whatever faraway land they sprang from.

It’s a crap shoot. But roll those dice they must, and for good reason. Who would have guessed wild-ass ideas like light beer and flavored vodka would have taken hold as they have? Who would have bet money that a medicinal German liqueur would come to dominate the shot market? Some failures are more memorable than others, and below we feature a trio of prominent contenders that fought the good fight then went down with more noise than usual.

Ripple

Ripple

The Lost Dauphin of Pop Wines

1960-1984 E&J Gallo Winery

The Name: Some armchair etymologists claim “ripple” was ‘30s bluesman slang for a type of cocktail, but if that were true it would surely have popped up in at least one old blues song, cocktail manual or slang dictionary, which it didn’t. More likely it just seemed like a nice name for a new kind of drink. Ripple is a pleasant word describing, as it does, liquid making a pretty motion.

The Concept: Ripple came to life as a wine maker’s attempt to seize a chunk of the youth market. Something light and fizzy that might appeal to novice drinkers who didn’t particularly care for the taste of hops, or alcohol for that matter. Early TV and radio spots called it a “new drink for lively people,” “the ice cold refresher with twice the pleasure,” and, a bit oddly, “the wine that winks back at you.” The glass of the bottle bore a distinctive ripple pattern but, tellingly, no mention of the E&J Gallo Winery. Following the booming success of the original Red flavor, Pear and Pagan Pink were introduced in the mid-60s.

The Rise: Gallo’s timing, it turned out, was better than they could have imagined. A new generation of drinkers was rising up, and these kids, who the media termed “hippies,” were keenly interested in rebelling against everything their parents stood for, including their choice of adult refreshment. And here was something new and different, even rebellious. The wine snobs said it wasn’t really wine and the grown-ups dismissed it as spiked punch in a bottle.

History has unjustly vilified Ripple as a wino wine. Social workers and other assorted handwringers of the day attached so much infamy to its name that one imagines it was some manner of vile high-proof elixir reeking of brimstone. In fact, Ripple was merely an artificially-flavored, lightly-carbonated sweet wine drink weighing in at 11%. It was a wine cooler (before they called it that) with a bit of a bite.

The winos of the day generally preferred Gallo’s more high-powered offerings: Night Train and Thunderbird. Ripple found much more acceptance with the younger set; it became the drink of choice for college kids (and their younger siblings) and made headway in the black community as well.

Ripple’s pop culture impact was considerable. Fred Sanford (Redd Foxx) of the popular sitcom Sandford and Son led the charge, declaring his beverage of choice “the national drink of Watts.” Fred improvised all sorts of splendid Ripple cocktails, including Mintchipple (mint julep and Ripple), Cripple (cream and Ripple), Champipple (Champagne and Ripple) and Manischipple (Manischewitz and Ripple).

Ripple was also immortalized in song: blues artist Dan Shoemake sang its praises, as did Arlo Guthrie, Gordon Lightfoot, Johnnie Johnson, Loudon Wainwright III, Hanoi Rocks, Motorhead and Easy-E.

The Fall: Why Gallo ceased production of Ripple in the mid-’80s is something of a mystery. The winery never bothered to explain, which isn’t surprising when you remember they refrained from putting their name on the bottle.

Some alcohol historians (hoochstorians, if you will) claim Ripple was ruthlessly purged in an attempt by Gallo to clean up its image. While it’s true that the winery was fancying up its product line (in 1974 they even went so far as to start selling wine with actual corks), the theory doesn’t ring true. If Gallo was really interested in polishing its name they would have put to bed the much more notorious Night Train and Thunderbird, both of which are produced to this day.

No, it was a shrinking market share that did Ripple in. The niche Ripple had seized was being squeezed on all sides by its Gallo siblings: the kids were turning to the sweeter and lighter Boone’s Farm and the aging hippies were graduating to Gallo’s cheap jug wines. Furthermore, Gallo wanted to make room for their new innocuous brand of wine coolers, Bartles & Jaymes, which rolled out the same year Ripple vanished. Ripple was the Gatsby of its day, a shady relative who was tolerated so long as he was raking in the dough, then promptly cast out when he fell on hard times.

Availability: Surviving bottles are extremely rare, to the degree that one optimistic gent attempted to sell an unopened bottle of Red Ripple for $5000 on Ebay. He didn’t get any takers, but Ripple can still boast an  impressive appreciation in value: unopened bottles (originally going for a buck) generally sell in the $150-$200 range.

impressive appreciation in value: unopened bottles (originally going for a buck) generally sell in the $150-$200 range.

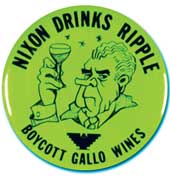

Trivia: During their long and bitter boycott of Gallo, the United Farm Workers released buttons claiming “Nixon Drinks Ripple.” Which probably wasn’t true.

Zima

Zima

The Monster That Would Not Die

1993-2008 Coors Brewing Co.

The Name: Zima means “winter” in a number of Slavic tongues.

The Concept: The marketing boys at Coors were certain they had a sure-fire winner on their hands when they unleashed Zima in 1993. It capitalized on not one, but two existing fads: the new “clear beverage craze” (remember Crystal Pepsi?) and the lingering wine-cooler rage. The fact that both fads were plainly diabolical didn’t bother them a hair; there was a great deal of coin to be made and whoever jumped in first would seize the high ground.

Their formula was simple: subtract taste and color from beer and add a vaguely citrus flavor. The 4.7% alcohol content, more than your average macrobrew, would surely put a stop in the gobs of those tiresome beerphiles thinking about calling it a sissy drink. Which was important because men of legal drinking age, the holy grail of the alcohol industry, were the primary target.

The Rise: Coors gambled a $50 million advertising budget and it paid off, at least initially. Despite the best efforts of their TV pitchman, a distinctly annoying gentleman with the disturbing tic of trading his Ss for Zs, a shocking 70% (according to Coors) of the American drinking public gave it a whirl. Coors moved a respectable 1.2 million barrels in the first year. Then things began to unravel.

The flaw in their formula was their focus. They spent their millions targeting a mythical demographic: legal-age males who hated the taste of beer, a group I imagine could be comfortably seated in an average high-school football stadium. After their shameful experimentation 0f ‘94, America’s males reconsidered the boundaries of their collective masculinity and sales of Zima fell off 60% the following year.

To nobody’s surprise, except perhaps for the boys in Coors’ marketing department, surveys began to reveal Zima’s true demographic: women and those who the alcohol industry likes to call “pre-legal consumers.”

It goes without saying that Coors was accused by the usual shrill gang of scolds as engaging in a cynical campaign targeting teenagers. Their proof? Teenagers were drinking it. Their logic being: if teenagers are doing something, then adults must be telling them to do it. Which, speaking as a former teenager myself, makes very little sense. Zima was also demonized as a gateway drink, a devilishly gentle ramp between angelic soda and sinister beer.

But like a rudely spurned yet insanely delusional groupie, Coors wasn’t ready to give up on full-grown men just yet. After the fall-off, Coors riposted with Zima Gold, which they swore, with a straight face, offered “a taste of bourbon.” Guys weren’t buying it, in both senses of the term, and it vanished within a year. Coors would doggedly try again with a pumped-up 5.9% Zima XXX (It’s exxxtremely exxxcellent!), but it also failed to gain a foothold with the boys.

The Fall: By so aggressively courting men, Coors gave them sole mandate to lay down judgment. And lay it down they did. With a healthy shove from David Letterman, who made zinging Zima a national pastime, the clear malt leapt into the American lexicon as a reflective term of ridicule and shame. A gentleman’s masculinity was no longer assailed with claims of milk sopping or tea sipping, no, those alleged zissies were zwilling Zima. Behind closed doors, of course. Zima allowed even light beer drinkers to feel macho and superior, which was a long, slow train coming.

Had Coors pitched more to women, men would have shrugged off Zima as a “chick thing” and would not have lambasted it so savagely — when was the last time you heard a guy get worked up about the relative quality of a particular brand of purse?

Despite almost universal derision by the public in general and the drinking press in particular (see Real Drunks Don’t Drink Zima MDM Nov. ‘96), Zima managed to gimp along for an astonishing 15 years. Like a scrappy poodle, it chased off a slew of imitators (including Stroh’s Clash and Miller’s Qube) before upstart Smirnoff Ice grabbed the lion’s share of the malternative turf in the early 2000s. Zima was mercifully put down in October 2008.

Availability: Since its demise was recent, you can probably get as much as you want at a good price. Just don’t tell your friends.

Availability: Since its demise was recent, you can probably get as much as you want at a good price. Just don’t tell your friends.

Trivia: Zima’s sales were helped along by an urban myth suggesting that a Zima swill-down wouldn’t register on a Breathalyzer. It should also be noted that the Zima pitchman set back the long-prophesied resurrection of the fedora by at least 50 years.

Billy Beer

Billy Beer

Second-Hand Celebrity Sells! Right?

1977-1979 Falls City Brewing (et al.)

The Name: Courtesy of President Jimmy Carter’s redneck brother Billy.

The Concept: Celebrity endorsement of alcohol has a long and largely successful history. Bogart did it, as did John Wayne, and need I mention Billy Dee Williams? Actually naming the product after the celebrity, however, is a bit more dicey. It’s worked for Willie Nelson, sure, but do you recall Three Stooges Beer? Elvira’s Night Brew? J.R. Ewing’s Private Stock? Me neither. The annals of alcohol history (and Ebay) are strewn with failed attempts at turning a famous name into something you’d want to put in your mouth.

But this was a natural. The shiny new president’s brother was a straight-up, unabashed, beer-swilling drunkard. He drank up to 10 six-packs a day, for crissakes — if there was ever a guy begging for a beer endorsement deal it was Billy Carter. Furthermore, Billy’s straight-talking, rough-hewn style seemed to resonate with the redneck community, and do you know what those hillbillies do? They guzzle beer. A helluva lot of beer. It was the kind of sweet deal that only an entirely new level of outright greed and blazing incompetence could screw up, and Falls City Brewing was more than ready to prove it was up to the task.

The Rise: “Maybe I’ll become the Colonel Sanders of beer,” said Billy Carter when his namesake was launched in late 1977. He followed that bold and blithe quip with that strange laugh of his, the same laugh that trailed similar statements, such as: “Hell, maybe I should run for president.”

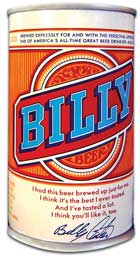

“I had this beer brewed just for me. I think it’s the best I ever tasted. And I’ve tasted a lot. I think you’ll like it too.” It said so right on the can. Whether Billy wrote or believed those words is uncertain, but he was certainly prepared to say that he did.

For its part, Falls City was not only willing to wager on the power of Billy Carter to sell beer, they pushed in all their chips. With the help of three other second-tier breweries, in the space of a year they cranked out an astounding 2 billion cans—that was nine-plus beers for every man, woman and child in the U.S.

Billy did his part, at first. A veteran pitchman (he was already raking in $300,000 a year showing up at promotions and events), he embarked on a whirlwind publicity tour and managed to say enough outrageous things to stay in the national spotlight. He even served Billy Beer at his daughter’s wedding and all 85 cases were dutifully consumed in the first hour.

It should be said that, for all his down-home buffoonery, Billy possessed a remarkable wit. He reeled off one-liners with the practiced ease of a professional comedian. Beneath it all, however, he was actually quite shy; he would later confess that he showed up drunk at most public events because he felt uncomfortable in front of crowds. It’s not such a stretch to compare Billy to Pagliacci: an intelligent and sensitive man hiding behind and disturbed by the clown mask that paid the bills.

The Fall: Billy Beer was not meant to last. It was a short con from the start. Falls City behaved like fast-talking snake-oil salesmen hoping to blow into a town long enough to skin the yokels then skip out before the hicks realized they were buying ditch water. Instead of brewing a quality beer befitting a standing president’s drunkard brother, they packaged the cheapest crap they could legally call beer and tried to unload as much as they could before the public got wise to the fact they were drinking bottom-of the-barrel swill.

Unfortunately for the brewery, the public got wise much sooner than expected. Despite millions of dollars of free publicity, things began to fall apart almost immediately. After the first round of curiosity buying, word got around and sales collapsed like a dynamited bridge.

Billy wasn’t exactly helping matters. One of the downsides of employing a “straight-talking” drunk is he’s likely to go off script. That’s providing he’s read the script. Or if he’s even aware there is a script. Billy had the nagging habit of getting up in front of a gang of reporters and confessing 1.) he still drank PBR and 2.) he must have been drunk when he chose the flavor of his own beer.

Billy wasn’t exactly helping matters. One of the downsides of employing a “straight-talking” drunk is he’s likely to go off script. That’s providing he’s read the script. Or if he’s even aware there is a script. Billy had the nagging habit of getting up in front of a gang of reporters and confessing 1.) he still drank PBR and 2.) he must have been drunk when he chose the flavor of his own beer.

It was akin to Pete Coors showing up at press conference sucking on a forty of Bud and declaring “Rocky Mountain spring water” was just fancy industry code for donkey urine. The fact that Falls City was paying Billy a paltry $50,000 a year for the use of his name and full-time promoting skills might have had more than a little to do with his eroding sense of loyalty.

The president of Falls City would later claim the beer “sank with the popularity of the President,” which is patent nonsense. All the second-hand popularity in the world wouldn’t have convinced beer drinkers to continue drinking that swill, not once they’d actually tried it.

Falls City didn’t just bet the farm — they bet the brewery. When all the hype and smoke finally cleared, they’d find themselves bankrupt.

The swindling would continue long after production ceased. Ads began appearing in newspapers and magazines declaring that a group of investors wished to pay hundreds, even thousands of dollars apiece for cans of Billy Beer. Strangely, those eager investors were very difficult to get a hold of. More suspiciously, the ads were followed by similar adverts offering to sell cans of Billy for a mere $50. This “salting-the-goldmine” ruse  caused a brief price spike among collectors, and otherwise sensible people started hoarding cans, hoping their stash would appreciate into a nice retirement fund, which it didn’t.

caused a brief price spike among collectors, and otherwise sensible people started hoarding cans, hoping their stash would appreciate into a nice retirement fund, which it didn’t.

Availability: A sizable share of those 2 billion cans have managed to survive. You can get a full can for as little as a buck, and a ringed six-pack for $10-$20.

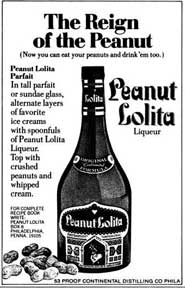

Trivia: Billy also pitched a peanut-flavored liqueur going by the slightly creepy ringer Peanut Lolita. Created by Continental Distilling purely to cash in on the Carter-era peanut craze, it went belly up in the late ‘70s.