Outside my home in Ilsan, South Korea is a pedestrian arcade we call “Meat Street.” It has a real name, but like all streets in Korea, nobody knows what it is.

Outside my home in Ilsan, South Korea is a pedestrian arcade we call “Meat Street.” It has a real name, but like all streets in Korea, nobody knows what it is.

On either side of Meat Street’s three blocks are an ugly five- and six-story buildings. On the ground floor is the meat: Korean barbecue mostly, but also fried chicken, raw fish, and other fat-filled horrors. Above the restaurants are the bars. There are hundreds of bars on Meat Street. Bars are stack on top of bars, next to other bars. Welcome to Apocalypse Ilsan.

Many of the bars are indistinguishable from each other, just typical Korean hofs (pubs). They have names like Alcohology, O Bar, and Ho Bars I-IV. There are places that pair fine scotch with squid and canned peaches, Bombay gin with Tater Tots.

Others are LP request bars, where you can chill out to seemingly endless tracks of Chris DeBurgh and Chicago over 17 bottles of Hite beer. Some are fusion bars, though what they’re attempting to fuse is unclear. It may be they’re fusing Western bar culture with Korean bar culture, and apparently that means sitting around an ivory table with three pitchers of Day-Glo soju cocktails and a plate of crackers and Kraft Singles with half a maraschino cherry plopped on top.

“If they are sad, or if they are happy, in our culture, we have to drink,” he says. “Everyone.”

As the sky darkens, Meat Street begins its nightly slide into depravity and decadence. The first to pass out are usually the younger salarymen, with their dark suits, crispy hair, and fire-engine red faces. They’re often found on park benches or spooning potted trees, their glasses askew, their heads resting on their arms. Their elders will join them soon enough. The college kids usually manage to keep going, marching through the night to the final climatic battle over cabs home. Taxis have their pick at this point. Usually, you’re forced to yell your destination through a cracked window—”Madu-dong!” “Daehwa-yok!” “Jungsan!”—and hope the driver decides he wants to go where you do.

By sunrise, it’s mostly over, except for a few loud shits who’ll keep going until they’re finally rolled out of the last bars and restaurants. Then it’s up to Ilsan’s silent heroes—the street cleaners—to deal with the aftermath. The pyramids of kimchi-tinted vomit. The bits of blood and hair left by eager young bucks fighting. A hundred cancers worth of cigarette butts. And business cards featuring enormously-titted Japanese porn stars, advertising full-service “massages,” with discounted group rates for ten or more men.

Sweep, sweep, go the street cleaners. The rest of the city wakes up, breathes the foul air, and says, “Ah . . . Tuesday.”

Soju Think You Can Drink?

Koreans drink like Hell.

According to the World Health Organization, South Korea is 13th in the world for drinking, consuming an annual 14.8 liters of pure alcohol per capita. According to the Japanese newspaper Asahi Shinbun, this puts them leagues ahead of both Japan (eight liters) and China (5.9 liters). They are the world’s biggest drinkers outside of Europe.

They are also the world’s number one spirit drinkers, thanks to the cult of soju. A mix of water and ethanol, soju’s alcohol content ranges from 32 to 50 proof. But even accounting for the fact it’s half-proof, Koreans still drink more spirit-based alcohol than the Russians, who come in second: 11.2 shots per week per person in Korea, versus an even five for the Russkies.

Jinro soju is the world’s number one selling spirit; Chumchurum soju is fourth, and 97% of those sales are in Korea. It retails cheap. A 350ml bottle at a corner store is $1.20, in a restaurant it’s $3.

Apart from soju, Koreans drink enormous amounts of beer, mostly the thin local varieties, though recently craft beer has gained a foothold. Brown liquor is more common amongst the upper classes. In 2011, Korea ranked first in consumption of super high-end whisky, most of it carelessly ingested in the form of boilermakers.

Unlike the rest of us, Koreans are honest about why they drink—they drink to get fucked up. They may try to impress their buddies by forking out for Glenfiddich 18 Year Old, but they know what they’re doing. Koreans don’t fool themselves, like we do, into believing they’re going out to have one or two, and then—whoops!—end up flat-faced on the floor. They set out to get flat-faced in the first place.

“I usually start from a barbecue place or any restaurants you can eat and drink at, and move on to the next places,” says Moon Sunyoung, 26, a tour guide and former bartender. “I don’t really have a typical place I finish because it could be anywhere, I get so drunk.”

The bartenders encourage it, unlike back home, where they’re expected to behave as social workers. “In the West, you shouldn’t sell drinks to people who are extremely drunk,” Moon says. “However in Korea, bartenders or waitresses give you drinks no matter how drunk you are. There is no regulation about the drink ‘limit’.”

Reid Cockburn, 40, from Ontario, set up The Whiskey Weasel, in Ilsan in 2011, and a second branch in Gangnam a year later. He’s since sold them, but he remembers it all well.

“With Koreans, if we cut them off and told them they’d had too much, the reaction could range from surprise to shock to anger, because it’s just not in the culture here to cut someone off when they’re really drunk,” Cockburn says. “And there’s generally not the stigma of being the drunk guy in the bar.”

Drinking Against the Void

There is a common feeling in Korea that you just have to drink, especially if you’re a man, but women are starting to get it too.

“If boys want to meet girls, they have to drink,” says Ray Nam, 25, manager of Cocky Pub in Ilsan. “If I don’t drink, I can’t meet my friends. If they want to play outside, want to hang out, they have to drink.

“If they are sad, or if they are happy, in our culture, we have to drink,” he says. “Everyone.”

The first time many Koreans get drunk is the day they finish the high-stakes soonool, the Korean university entrance exams. They continue to drink throughout their lives. The most anti-social and obnoxious drunks are often the elderly.

Stress is a key reason for the heavy drinking. Statistically, Koreans spend more time at work than any of their OECD[1] colleagues. (Though how much they accomplish there is a matter of debate.) They also face enormous societal pressures, like getting married at the right age, getting the right job, having the right kids, pleasing overbearing relatives, fulfilling traditional roles they never asked for, and paying for it all. Suicide is endemic, evangelical Christianity is huge, and for those who don’t jump off bridges or pray all day, the alternative is to get completely shit-faced.

Lee Min-seok, 29, works at a start-up company in Seoul. He says stress is paramount. “There aren’t any other alternatives except for drinking to release that stress. There’s no outlet.”

Euny Hong, the Korean-American author of The Birth of Korean Cool, puts it down to han, a feeling of unresolved anger most Koreans have.

“They have a hereditary wrath of the generations,” Hong says, “and its origins far predate one’s birth, so there’s no one you can really take vengeance upon or complain to. There’s no built-in catharsis, and things like therapy are frowned upon, so drinking is a natural alternative.”

But Lee thinks the role of han is overstated. “It’s just stress. From work, from life.”

“Alcohol long ago sneaked into the culture and became an essential part of long-standing rituals in extended family and village situations and with work colleagues,” says Michael Breen, the British author of The Koreans and Kim Jong-Il: North Korea’s Dear Leader. “There’s a risk when you decline a drink that you a.) offend the senior guy in the group, b.) offend the nice person pouring your drink, and c.) sour the group atmosphere. Given this triple whammy, most take the road more traveled and get legless with the rest.”

Koreans get famously sentimental when they drink, and often times you find yourself playing elbows and knees with the (otherwise heterosexual) guy sitting next to you, as his hands start to grab at your arms, legs, and chest, while he tells you how much he loves you.

“The two go hand in hand—Korean sentimentality and alcohol,” says Jeong Junghee, 43, the owner of Jack Beer and Pocha in Ilsan. “It’s not frowned upon as a social vice. The drinking culture has more of a positive connotation or a positive light to it. Koreans will drink to celebrate something good. They will drink to mourn something bad.”

Never Drink on an Empty Stomach

Koreans almost always drink with food. Not having anjou—basically translated, “drinking food”—means you have had a really shit day.

“It’s shameful if they don’t order food,” says Nam. “Koreans order lots of food…they have to order at least one dish at their table. Even if they don’t eat it.”

Anjou can be expensive, but it’s where many bars make their money. A recent “well-being” health fad has meant more focus on the anjou, as if a plate of sausages or squid will somehow mitigate the heavy drinking.

Apart from food, there are the other social rituals that go with drinking, especially drinking soju. You should always pour for the eldest person at the table first, with two hands. When accepting a drink from an elder, you should hold the glass with two hands, or with your left hand under your right arm, like you’re holding your sleeve. You turn your face to the side when you drink in front of an elder. And you never, ever pour your own drink or let someone else’s glass go empty too long.

Although Lee doesn’t worry too much about these rules with his friends, he follows them to the letter in other situations. “I tend to be conscious about those rules in front of business colleagues. For me, it shows how civilized and well-educated you are,” Lee says. He also follows them closely when he drinks with his dad. “It’s about respect.”

Hong is blunter. The drinking rules “are very important, because the framework of all the etiquette removes some of the guilt of overindulgence.”

Drinking with the Boss

Part and parcel of drinking is a custom called hwesik. It’s largely untranslatable, but it basically means getting drunk with the boss and the rest of your work team. It works something like this: close to quitting time, often 9 or 10pm, the boss decides he feels like tying one on. He tells his workers they’re all going boozing, and everyone drops everything and goes out—no questions asked. It’s equally a form of team building and proving your loyalty to your department’s Tyrant-in-Chief.

“I really dislike hwesik,” says Paul Thompson, 28, a teacher from Pennsylvania. “For my current company when we do them, it’s a little more laid back…but when we did them in Seoul, you just had to drink and continue drinking as long as the boss wanted to drink, and that was just a pain the ass. If you want to stop drinking, you’re not really allowed to.”

On the bright side, the boss does pick up the tab.

It’s all seen as a form of bonding, says Breen: “There’s a saying to the effect that if you lunch together, you can be acquaintances, if you dine together you can be friends, but if you get drunk together you become real blood-brothers.”

A Night Out in Seoul

To give you a proper perspective of drinking in Korea, I took eight friends on a research mission in Jongno, an entertainment district in central Seoul. Though there are a half-dozen or so major drinking areas in the city, we chose Jongno because it’s older, more popular with locals than tourists and gets more salarymen than students.

#1: The Table

The Table is a newish, basement brewpub with the motto, “People, beer, food, joy,” emblazoned at the entrance. The craft beer scene is blowing up in Seoul, and we enjoyed very passable honey brown ales, pilsners, stouts, and other beers that five years ago were impossible to find in Korea. The waiter let us get by without buying food. The décor looks like the stage of the Golden Globes, and roughly half the customers were consumed with the task of impressing very bored-looking dates.

#2: The Jongno Tavern

#2: The Jongno Tavern

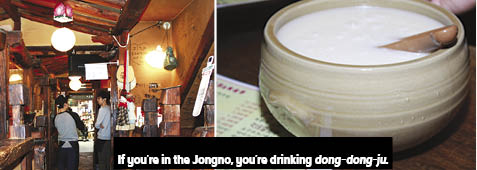

Dong-dong-ju and makkoli are traditional milky rice wines. Though they’re supposed to be different, no one can tell you how. We ordered two large pails of dong-dong-ju—along with steamed tofu and kimchi, at the insistence of the management.

The point of the Jongno Tavern is to remind you how Koreans drank 250 years ago. You sense an almost desperate overreach for authenticity—rough-hewn wood tables, graffiti on the plank walls, ceramic pots for the booze—similar to the suburban Irish pubs back home. Most of the customers were college kids, and good on them.

#3: Barbecue Joint

The heart of the Korean drinking experience is the barbecue restaurant. Usually it’s the first stop and is where the serious drinking takes place. Soju, shitty beer, and soju-dropped-in-shitty beer are the preferred methods, paired up with slabs of pork and beef wrapped with kimchi in lettuce leaves. We were lucky enough to find a proper, old-time barbecue joint—large, loud, and dark with coals brought in from a furnace outside and communication with wait-staff done by yelling. It’s outside the barbecue restaurants that the first victims are usually found passed out in the road. Meals can take hours to finish, and the whole experience is reminiscent of a Roman vomitorium, with mounds of food, legions of empty bottles, and sick drinkers outside, voiding themselves for the next round.

#4: GS 25

If barbecue is the heart of Korean drinking than knocking them back outside the corner store is its bruised skin. Across the country, 7-11s, CUs, and GS 25s set up tables and chairs outside their doors so drunks can have one or two or three for the road, under the starry skies. We were lucky to find a GS 25 with an empty picnic table in front of it. When we tried to clean it ourselves, the ownership freaked out and dashed out to do it for us. We drank a tall boy each, and as much as we were enjoying it, we had to move on. Foreigners especially are known to spend entire nights drinking at the corner store, and we certainly didn’t want to be lumped in with that lot.

#5: The Makkoli Shack in Insadong

Insadong is a 500-year-old neighborhood in Jongno that was once home to Korean civil servants, but since has been turned into a Disneyfied Tourist Hell of cheap knickknacks and overpriced “authentic” food. Except for one alley, called Pimagol. Though not preserved from the Chosun Dynasty, is at least preserved from the 1980s, when the area was more famous for its prostitutes and bars than its hordes of gawking Germans.

The Makkoli Shack is regarded by many—including myself—as the best bar in Seoul. Its official name is Jongno House, but nobody knows that. Around since the mid-50s, students have planned revolutions at its tables, millions of punters have gotten drunk in its underground, divey interior, and today it remains impressively free of gentrification. Rather than the ornate ceramic bowls you get elsewhere, makkoli here is served in steel pails, the kind you use for fishing or transporting cement. You don’t order it—it’s brought to your table whether you want it or not, along with a plate of fried mackerel. There are other foods and drinks available, but few bother. An hour here costs $6, the waitress is about 105 years old, and it’s nearly impossible to find from the road, so you better know where you’re going.

#6: Pojang Macha (soju tent)

The soju tent is fast becoming a lost cultural treasure. The government, in its unceasing efforts to strip any and all character from the country, has largely banned the big orange drinking tents as reminders of Korea’s recent underdevelopment. A certain road, squeezed between two rows of high-rises in Jongno, is one of the last places you’ll find them. They have the feel of museum pieces rather than the authentic soju tents of old, but as a glimpse into a not-too-distant past, they’re wonderful. We ordered soju, beer, and fresh fish cooked over a Primus stove. The tents were packed, but despite their popularity, no one knows how long the government will let them stick around. So get in them while you can.

#7: Ozone

A cocktail bar with an English menu, small, American-sized bottles of beer, and a DJ who will play whatever your black foreign heart requests. The $6 vodka tonics go down pretty easily after a night of nothing but beer, makkoli, and soju. For years, Koreans only ordered whole bottles of liquor, which they could sometimes store behind the bar if they didn’t finish them in one go. Places like Ozone were the first to realize how much profit is made from individual cocktails and shots. Ozone was a favorite of mine after I was banned from Rockers, a similar bar down the road.

#8: Rockers

The owner of this dark LP bar possesses a deep knowledge of 60s and 70s rock and will play your requests. I was a regular here for a year until I was asked to leave after a fight with a drunk who thought I was a GI. I went unrecognized.

#9: Noraebang

Any proper night of drinking in Korea ends with noraebang—the karaoke room. The Koreans have blissfully learned to put karaoke in its place—away from where other people can hear it. You rent rooms by the hour, and yes, people fuck in them. Koreans love singing at the end of the night, but I hate it. There’s little worse than ending your night with an off-key version of “We Built This City” or “Holly Holy” pounding through your skull.

The Future of Drinking in Free Korea

Toronto native Ian White, 28, plays guitar for the Seoul hardcore band Yuppie Killer. When I asked him why Koreans drink so much, he turned the question around.

“I think the more pertinent question is, what are the times the Koreans don’t drink?” he says. “It’s a fucking depressing country, what with the mangled architecture, the weird unholy bastard union between Confucianist values and rampant drive-hard capitalism that is brought on by years of dictatorship.”

White rues the fact there are no illegal drugs available, and says that even in punk rock, after a show, everyone has to go “from one shitty, overpriced Chinese or kimchi jiggae place to another for two or three hours.”

“Nobody ever has a sip of soju and says, ‘Mmm, yeah, that really hit the spot,’” White says. “No, you take a big-ass swig, because it’s so crappy, and the only thing that makes it worthwhile is overdoing it.”

Breen agrees. “The objective in these situations is not hedonistic—it’s not to tickle the palate with fine flavors,” he says. It’s “to get rat-faced.”

Then there’s the question of whether Koreans really do out-drink foreigners cup for cup. Although it certainly appears Koreans drink more in one sitting, Cockburn, in his years of tending bar in Korea, isn’t sure that’s really the case.

“In my experience, when Koreans get together they will drink very quickly and get drunk, and then they’ll kind of level off,” Cockburn says. “But with Americans, they will start off slow, gradually build up their drunkenness. And then the shots come out and they really start pounding it. It’s like two processes of reaching the same level.”

Cockburn thinks the difference in statistics is because Koreans get drunk midweek too, whereas Westerners generally keep their binging to the weekends.

The Korean government has started recognizing this as a problem and have instituted programs to try to stop Koreans from drinking so hard all the time. A recent proposal to ban drinking in public is currently in committee. Hite-Jinro, the country’s number-one manufacturer of soju and beer, has started putting warning labels on their products, asking drinkers not to fight when they drink. Samsung and other companies have started the 1-1-9 Program for hwesik, meaning one type of alcohol, one venue, and home by nine.

It’s unlikely any of this will work, or at least it seems so to me. Most office workers don’t leave work before nine, never mind making it home by then. Warning labels might work on teenagers, but adults will respond first to the demands of their coworkers, bosses, and older friends before they follow an anonymous warning on a bottle. And the only likely way to cut heavy drinking, higher taxes on alcohol, has been ruled out by the government.

But Breen is less cynical than I.

“In the days when people would spend 15 hours a day, six days a week at the office, productivity was not a concern,” he says. But Breen feels the workplace is changing, so the culture will too. “Now, with the eight hour day, five day work week, and increased leisure, it is. Also, the government cares more about health care than it did. So government and corporations are more motivated to discourage excessive drinking. Will they be successful? I think so because the wind is already blowing in that direction.”

He also notes that with more women in the workplace, boys can’t get up to the naughtiness they used to. Still, in my experience, a real eight-hour workday seems at least a decade away.

Moon Sunyoung, the young tour guide, sees it simply as part of Korean life, like kimchi, spending 13 hours a day at work, and always being on the verge of nuclear annihilation.

“I’d never actually known Koreans were famous for their drinking until I heard it from foreigners,” she says. “I guess it’s because I grew up with it and it has been just so natural. Koreans drink a lot but mostly for just having good times with others and not because we are all alcoholics.”

[1] The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development