No one is certain where or when Ernest Hemingway began his long relationship with the tall silver flask he called Jinny, but a handful of clues are revealed in a passage from True at First Light, his posthumous semi-fictional memoir set during a 1953 safari with his fourth wife Mary.

“The Jinny flask was in one pocket of the old Spanish double cartridge pouches. It was a pint bottle of Gordon’s we had bought at Sultan Hamud and it was named after another old famous silver flask that had finally opened its seams at too many thousand feet during a war and had caused me to believe for a moment that I had been hit in the buttocks. The old Jinny flask had never repaired properly but we had named this squat pint bottle for the old tall hip-fitting flask that bore the name of a girl on its silver screw top and bore no names of the fights where it had been present nor any names of those who had drunk from it and now were dead. The battles and the names would have covered both sides of the old Jinny flask if they had been engraved in modest size.”

There is little doubt in my mind that the name inscribed on the flask’s cap belonged to Virginia “Jinny” Pfeiffer, the younger sister of Hemingway’s second wife Pauline. Jinny had a deep, somewhat strange history with Hemingway, and it’s likely she either gifted the inscribed flask to Hemingway, or Hemingway—somewhat scandalously—decided to have his sister-in-law’s name engraved on his favorite flask.

There is little doubt in my mind that the name inscribed on the flask’s cap belonged to Virginia “Jinny” Pfeiffer, the younger sister of Hemingway’s second wife Pauline. Jinny had a deep, somewhat strange history with Hemingway, and it’s likely she either gifted the inscribed flask to Hemingway, or Hemingway—somewhat scandalously—decided to have his sister-in-law’s name engraved on his favorite flask.

Either is a possibility: the former because Jinny and Hemingway were close friends for fifteen years (1925-1940), right up until he divorced Pauline. And the latter because, from the start, Hemingway was more attracted to Jinny than her sister, but was thwarted by the fact that Jinny preferred the company of women. But perhaps not exclusively: according to Ruth Hawkins, author of Unbelievable Happiness and Final Sorrow: The Hemingway-Pfeiffer Marriage, there is strong evidence that Jinny and Ernest conducted a clandestine affair, and Hemingway’s tragic and top-rate short story “The Sea Change” was a eulogy to that doomed relationship.

Further complicating their relationship was Jinny’s role as Papa’s personal homewrecker. First, at the behest of her sister, she helped sabotage Hemingway’s first marriage to their erstwhile pal Hadley, then, 13 years later, caused the breakup of his marriage to sister Pauline by spreading rumors (almost certainly true) that Hemingway was having a torrid affair with fellow war correspondent and future wife Martha Gellhorn.

What’s also interesting and more than a little odd is the inscription was on the cap of the flask. An inscription on the body would have been there for all to see, especially if someone, perhaps your wife, were putting the flask to use. An inscription on the cap, on the other hand, would give the owner the option of palming the evidence before handing over the hooch.

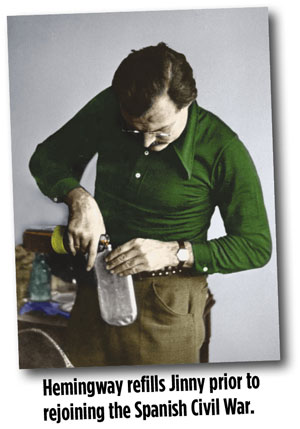

So, whether simply a gift from an admiring sister-in-law or a memento of a taboo relationship, we know the Jinny flask was with Hemingway when he covered the Spanish Civil War in 1937. A number of photos (see right) show him with the flask, and journalist Vincent Sheean would describe his first (but not last) encounter with Jinny in his 1939 memoir Not Peace But a Sword:

So, whether simply a gift from an admiring sister-in-law or a memento of a taboo relationship, we know the Jinny flask was with Hemingway when he covered the Spanish Civil War in 1937. A number of photos (see right) show him with the flask, and journalist Vincent Sheean would describe his first (but not last) encounter with Jinny in his 1939 memoir Not Peace But a Sword:

“This flask, a battered silver contraption of great cubic capacity, must have had a long career in its owner’s service. It had developed a certain flexibility with the passage of years, and when rhythmically pressed between the thumb and forefinger it emitted a tomtom noise like the drums that accompany a Moorish dancing girl. I saw it afterwards under a variety of conditions in Spain, and always with pleasure. The old flask must have been a welcome sight to many besides myself, for it was as inexhaustible as its owner, and as generous.”

From the photos and Sheean’s description, we can ascertain that Jinny had been in the saddle well before its arrival in Spain. A silver flask is mentioned in many of Hemingway’s books and stories, starting in the early ‘30s, and was seen in his possession as he observed the D-Day assault from the deck of a landing craft.

The war during which Jinny “finally opened its seams at too many thousand feet” was almost certainly World War II. After charging around France, liberating hotels and their wine cellars from the Nazis, and participating in more than one bloody battle, Hemingway took a long flight home to the US, during which Jinny most likely ruptured.

In 1950, Hemingway was famously described drinking from a silver flask by Lillian Ross in her book, Portrait of Hemingway, but since Jinny had been retired, it was most likely the flask described by Hemingway friend A.E. Hotchner in his bio Papa Hemingway. A gift from his fourth and final wife, it bore the inscription: “From Mary with Love,” contained “splendidly-aged Calvados” and is presently being hoarded by the JFK Presidential Library and Museum.