A hip flask is a container for liquor like a Molotov cocktail is a bottle for gasoline.

If you’ve carried the former or hurled the latter (or more poignantly, had one hurled at you) you know their barest definitions leave a helluva lot of meaning off the table.

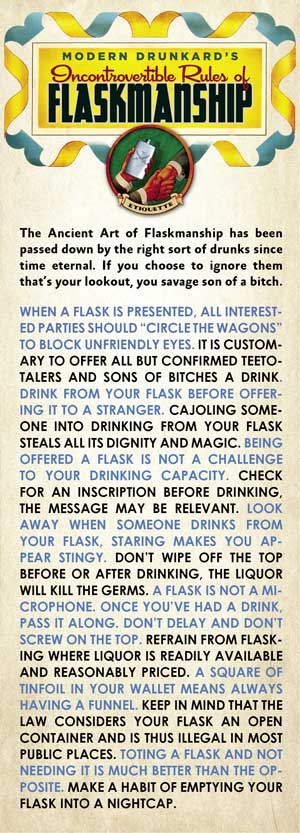

The fact that both—when put to their intended uses—are illegal in most public places tells you something. As does the unique shape of the hip flask, designed as it is to be hidden next to the human body, shielded from the prying eyes of prigs and policemen alike.

Handmaiden of Hooch, Ally of Humankind

During its long journey as humanity’s constant, sometimes clandestine companion, the flask has played myriad roles: it lent strength to those stabbing at the fringes of civilization, it served as a peerless greeting between travelers on perilous roads, it went to war as standard issue for millions of soldiers, it sealed peace treaties, giving solace to the defeated and joy to the victors, it was a weapon in the war against tyranny. When the cold and callous hand of Prohibition gripped the land, flasks transformed into the Molotov cocktails of the resistance, igniting a fearful society with fiery defiance.

It has bolstered innumerable grooms wavering at the altar, hunters shivering in their blinds and sports fans huddled in the stands. It makes long trips seem less so, coloring in those broad blank spaces between places you want to be. Great American heroes with presidential ambitions gave them out as reminders to vote for the right sort of person, brothers Frank and Jesse used them to steel their resolve before their bold robberies, Blackbeard loaded his with rum and gunpowder, both Roman legionnaires and Imperial German infantrymen carried them as part of their standard issue when they picked a fight with the world. You were as likely to find one in the pockets of the Lost Generation’s brightest lights as you were a pencil, and at least one pope (Pope Pius XII) carried a flask of wine under his robes, “for medical reasons.”

It is a powerful talisman for repelling prudes you shouldn’t waste your time with, and attracting bon vivants you definitely want to know. It provides the grease, clandestinely applied, that lets you slide eel-like through tight, uncomfortable and tedious situations. It is a discrete source of strength when you’re under the yoke and a great yawp of joy when you’re running free.

A Crude Awakening

So I wish in heav’n his soul may dwell,

That first found out the leather bottel.

—Traditional Anglo-Saxon Tavern Song

The earliest ancestor of the flask, the Stone Age mead skin, was probably invented about 15 minutes after the first batch of mead was thrown together.Why not take this fine elixir with me wherever I go from now on? the original meadman surely must have wondered while dumping out the vile water clogging a container probably constructed of animal skin or bladder.

Sealed and cured with beeswax, the skin becomes quite stiff, which serves to alleviate pressure on the plug. It undoubtedly featured a sling because mankind, if you can believe it, hadn’t invented pockets yet and wouldn’t for a very long time.

Canteens of the Gods

Canteens of the Gods

Perhaps ironically, it was religious fervor that moved flask production from the craftsman’s shop to the factory. Pre-Christian pilgrims, after trekking long and far to a holy site, wanted some sort of souvenir to take home to remind them of their good deed and perhaps flaunt in the face of those less pious and ambulatory. And since many of the holy sites featured some sort of holy (perhaps healing) water source, the pilgrim flask was born. They were usually constructed of baked clay, flat, round, fitted with rope loops and usually decorated with religious motifs. Sometimes, instead of water, a pilgrim could buy one filled with holy (and certainly healing) wine, especially if he or she were visiting a site paying homage to Dionysus or Bacchus.

As religion became more organized and pilgrimages became more popular, pottery factories, usually employing molds, began popping up, first near the holy sites then later in large port cities where huge merchant fleets would export thousands of flasks to whichever holy site wanted them. These factories also produced a variety of similar secular flasks: one of the more popular lines, featuring pictorials of gladiatorial combat, were filled with wine and sold in Roman coliseums.

Pilgrim flasks became so commonplace that nearly  every God-fearing household had at least one on a shelf, a memento of a holy road trip. And certainly some were put to use as alcohol flasks, which has caused some historians to foolishly suggest that the modern hip flask is a direct if warped descendant of the wholesome pilgrim flask. Which is like saying the modern battle rifle is a descendant of the toy musket, rather than the real muskets that were around at the same time.

every God-fearing household had at least one on a shelf, a memento of a holy road trip. And certainly some were put to use as alcohol flasks, which has caused some historians to foolishly suggest that the modern hip flask is a direct if warped descendant of the wholesome pilgrim flask. Which is like saying the modern battle rifle is a descendant of the toy musket, rather than the real muskets that were around at the same time.

While the upper classes experimented with flasks made of glass and metal, the rugged and cheap earthenware flask, along with its animal skin predecessors, would remain the wine, mead and ale carriers of choice for the common folk until well into the 17th century.

The Pocket Flask Arrives

“Small flasks to hold distilled spirits were useful traveling accouterments during a period when water was unsafe to drink and wine, ale and beer spoiled quickly.” —The Complete Peerage

Two major inventions had to go down before the proper pocket flask could rise up: distillation and pockets. Fortuitously enough, they became commonplace at around the same time.

Though beverage distillation had taken root in Italy during the 13th century, it took its own sweet time spreading across the rest of the continent. Boiling wine to a high proof was generally considered a goofy (and quite dangerous) trick performed by alchemists; hard alcohol wasn’t put on a firm commercial footing until the 17th century, and even then it was usually sold as a medicinal agent.

Then, slowly, certain people (your and my direct ancestors no doubt) got the idea that this booming new body tonic was also good for lubricating the mood and mind, and suddenly the industry exploded like one of those early stills that were always exploding.

Excellent new boozes, including gin, vodka and whiskey, came onto the scene, and flask use (and production) jumped sharply as liquor became more affordable.

Suddenly a traveler didn’t need a huge honking canteen of wine, mead or ale to reach that fine level of satisfaction between destinations. A small container of concentrated alcohol, small enough to fit in one of those newfangled pockets, could do the job.

It isn’t the easiest thing to wrap your head around: we once walked around without pockets. Up until the 1600s, those who needed to carry small objects, such as coins, would put them in pouches which would be tied to their belts with string. Which made them easy prey for the “cut purses” who would sidle up, cut the string and make off with the loot. Finally, some canny tailor fell upon the idea of sewing pouches inside the trousers and jackets of the day, at once making your possessions harder to detect and take.

The first true pocket flasks appeared at the beginning of 18th century, and were generally shaped like a flattened egg, something that could be easily slipped in and out of said pockets.

Though every aristocrat who considered himself a man-about-town simply had to have one, an educated guess places the fast evolution of the flask not in the pockets of upper-class scoundrels but rather in the knapsacks of professional soldiers. By this time, the spirits flask was an essential part of a soldier’s gear, especially if that soldier was of the professional class, as opposed to a conscript.

It was the soldiers, especially the infantry who carried everything on their backs, who relied upon small-quantity vessels to provide warmth, motivation, courage and disinfection while on campaign. Furthermore, many of the improvements made to pocket flasks already had a precedent in a different sort of flask carried by soldiers.

Fill Your Powder Horns with Whiskey: Transmutable Flasks

“Fearsome and fearless, he (Blackbeard) sprinkled gunpowder into a flask of rum, ignited the drink and guzzled it while it popped and burned.” —C.C. Tsutsumi

Just as some flasks started as holy souvenirs, others began as implements of war. With the dawn of gunpowder and musketry, powder flasks became commonplace on battlefields and hunting grounds alike. Their design mirrored the pocket flask and sometimes the only way to tell them apart was the powder flask’s narrow nozzle for injecting powder into a barrel. Keeping your powder dry was absolutely essential, so these flasks tended to be watertight, making the transition to spirits flask as simple changing out the nozzle for something a bit wider.

Once the war—or a soldier’s career—was over, many a vet continued to carry his wartime companion with him, now loaded with a different sort of conflagration. As one 19th-century song instructed:

The fight is over, boys

So dump your powder

And fill your horns with cheer.

We can guess what kind of cheer they were singing about.

Some flasks were repurposed by design. Beginning in the 19th century, some women’s perfume makers began selling their pricey product in what were plainly spirits flasks. This is marketing at its cleverest: a husband was much more likely to spring for an expensive scent if it meant he got a silver flask at the tail end of the deal.

A Flask for Every Pocket

A Flask for Every Pocket

“General Taylor never surrenders.”

—Slogan on 1848 glass whiskey flask saluting future President Zachary Taylor’s leadership in the Mexican-American War

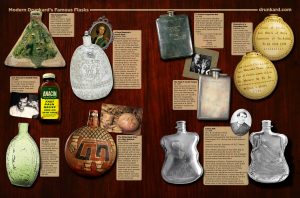

On the other side of the Atlantic, a flask revolution was brewing. In the early 1800s, a booming glass industry sprung up in the States, and they knew what sort of glassware Americans wanted. Nineteenth-century America was a nation on the go, and they couldn’t be expected to lurch westward with full-sized bottles of whiskey stuck in their belts. So they flooded the country with what collectors now call “historical flasks.” Molded, thick walled, and available in a rainbow of colors, they were soon found in the pocket of nearly every man west of the Mississippi and quite a few on the other side.

Up until the Civil War, these flasks were usually molded with uniquely American motifs, including the faces of favored presidents, eagles, flags, log cabins and sometimes political slogans. Filled with spirits (usually whiskey) and sold at the local version of the pub or liquor store, they could be refilled from the store’s barrels, much like the beer growlers of today.

Some bring a high premium at auction: an example bearing the visage of President Andrew Jackson recently brought $151,000. Pretty good considering it went for about a buck back in 1820.

The fact that Jackson was running for President at that time reveals two other uses for the flask: advertising tool and political schwag. Imagine if a present-day presidential candidate had the good taste to put his face on bottles of whiskey and give them out at rallies. How long would it be before they stuck him in a cage “for his own good?”

Now that glass was widely available and dead cheap, the wealthy moved on to precious metals as the material of choice, especially silver. Silver was long believed to have a purifying effect, making bad liquor taste better and good liquor taste fantastico.

Furthermore, now that every Tom, Dick and Harry had one, the rich naturally felt goaded into wanting extra special flasks with all sorts of goo-gahs and refinements. In a relatively narrow period of time, a shocking array of structural improvements came into play.

Fast-action bayonet caps and screw tops now employed cork to prevent embarrassing leaks. Hinged captive caps put an end to losing your top in a moment of euphoria. Detachable drinking cups covered the cap or hugged the bottom half of the flask. Peek-a-boo windows let you know exactly how much booze you had left and secret locking mechanisms kept unwanted lips off your liquor. Some came equipped with a fitted compass, in case you got lost on your way back home from the party. Material hybrid flasks became commonplace. A higher-end model might consist of four different materials, including glass, metal, leather, cork, wood, crystal, ivory or reptile skin.

The basic shape of the flask underwent rapid mutation as well. Two cappers came with separate compartments for different liquors. Long cylindrical hunting flasks appeared, sheathed in leather scabbards easily hung from a saddle. Specially-shaped flasks were contoured to fit wherever you felt the need to put them, including your boot, belt, coat pocket and even the newly-named hip pocket.

Yet still, when the Victorian Age ended and we crossed over in the 20th century, they were not yet called hip flasks.

Black-Jacks and Batwings

“Another name for the flask is foresight.” —William Juniper

The word flask itself surfaced around 1300, after centuries of going by close relatives flasca, flasko, flaxe, flasque and so on, all of which were descendants of a Teutonic borrowing of Latin. Or visa-versa, depending upon which etymologist you want to argue with.

It was a long circuitous route from flask to hip flask. Circa 1700, as liquor came into fashion, flasks were usually identified by what they carried: brandy flask, whisky flask, or the more general spirits flask.

Once we had pockets sussed out, we started calling them pocket flasks, then, as we starting naming our pockets, it was expanded to hip pocket flask, then finally contracted to hip flask around 1920.

As with all things semi-secret and associated with muse alcohol, a battery of slang terms have been used to describe the flask, including hipper, travel bottle, pocket rocket, batwing, mini, betty, rum-skin, black-jack, jingleboy, a-bit-on-the-hip, mickey, monkey, and pocket pistol. During World War II, RAF flyers would wryly flip the latter on its head and refer to their service revolvers as hip flasks.

If you carried a flask you were a vial villain, hipper, hip-flask fellow, a gentleman from Kentucky, or suffering from hip disease.

When U.S. Prohibition turned a large swath of Americans into active criminals, an oblique “Who goes there?” challenge system emerged. Any man who wasn’t a Dry carried a flask as surely as he would his wallet, but there were enemy agents about so you had to play it safe. If you noticed a tell-tale bulge in someone’s profile, you said, “You, suh, have the build of a gentleman from Ol’ Kentucky.” Or: “Mighty dry this season, the fields sure do need some irrigating.”

So long as your weren’t dealing with an obtuse farmer, you were likely to get a taste.

The Great Flask Shortage of 1920

“A hot-water bag will answer the purpose until something more artistic can be found.” —The Evening Public Ledger

More flasks were sold in the first six months of Prohibition than during the entire previous decade.

Flask manufacturers had girded themselves but were nowhere near ready for the ravenous mob clamoring for their wares once the saloons were shut. Shortages gave rise to wild improvisation: hot water bottles were rushed into service, as were baby bottles. They had the advantage of being disguised, but it was hard to appear suave and sophisticated while drinking from either.

“Wholesale and retail dealers in silverware say that one bright spot in their business,” reported the Washington Herald in 1922, “has been the demand for silver hip flasks. Hundreds of thousands have been bought for Christmas presents.”

Once production had cranked up enough to meet demand and create a sense of competition, the flask’s DNA underwent major shifts. Just as the medical and martial fields tend to make rapid gains during wartime, hip flask design made leaps and bounds after the government declared war on alcohol.

Are You Changing a Tire or Throwing a Party?

“Hip flasks will be worn concealed this season. It has been become established that every well-dressed man has one and display is no longer necessary.” —What’s In, What’s Out: 1922

Where before flasks were flashy playthings casually tucked away to avoid offending proper society, they now had to be near-invisible so as to avoid arrest and imprisonment. The once whimsical art of camouflaging flasks now expanded into a broad science. Almost any object smaller than a breadbox (and some things quite larger) might be an impostor housing liquor, including canes, hats, cigarette cases, spare car tires, cigars, fountain pens, books, articles of clothing, shoes, work tools, foodstuffs and so forth. Anything a citizen could carry down a street without arousing undue suspicion or ridicule became a model for a crypto-flask.

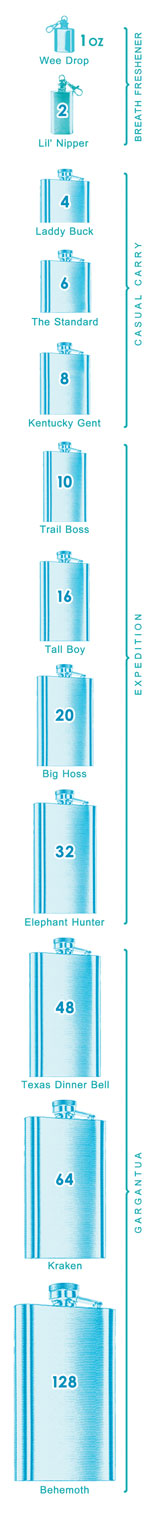

Another thick branch of mutation was the arrival of the Gargantua class of flask. The distances between civilized places to drink had become vast morbid deserts, so naturally the flasks would have to carry more sustenance for the journey. Suddenly a 64 ounce flask didn’t seem all that crazy, and even a hulking 128 ouncer spoke more to necessity than novelty.

In the early days of Prohibition, before speakeasies began blossoming like desert roses, a flask wasn’t just a thing to get you from one party to another, it was the party. And with so much booze on the move, a party could break out anywhere drinkers should meet, as evidenced by this portion of a 1920 poem by popular Washington Herald columnist O.O. McIntyre:

And then the party started

And there were ten flasks

Removed from the hip

In that many seconds

And the way they drank it

One would get the idea

That this was a free country

Metal flasks quickly seized turf from their glass counterparts, for several good reasons. If you were to take a spill, as sometimes happens when filled to the brim with joy, there was not only the danger of it breaking and severing an artery, but the added insult of attracting Johnny Law. If you lived in the Big Apple there was also the fresh menace of the recently installed subway turnstiles. Their thigh-high “arms” seemed specifically designed to smash glass flasks carried on the hip. After a wave of complaints, the metro authority rather snidely advised commuters to walk through backwards.

Furthermore, “hip-hitting” became a popular pastime for cops on the beat: upon noticing a suspicious bulge on a citizen’s hip, the officer would strike it hard with his nightstick, causing a glass flask (and any hopes for a swell evening) to shatter.

Naturally, a special flask was constructed specifically to resist these rude attacks. Called the Dreadnought, a Philadelphia daily reported it was “a brute for punishment,” “constructed with an extra covering of silver,” and “the most resounding blow has no effect.” The only disadvantage was “when struck by some hard object, such as a policeman’s club, a faint musical note can be heard.”

The Flask as Status Symbol

“Pocket Flask Are New Rage: Debutantes Demand Jeweled Containers”

—Headline, Seattle Star, 1922

Flasks quickly became status symbols. If you didn’t give a damn about your reputation, you could shuffle into a drug store and pick up a cheap tin affair for a dime. Contrarily, you could march into a jewelers and pony up for something that suggested a more airy station in life. T. Coleman du Pont, of the insanely wealthy du Pont clan, hipped his gin (for purely medicinal reasons, natch)* in a gold flask worth $15K in today’s dollars.

*“I am under orders from my physician to take a little sip when fatigued. Understand me, I take my gin as a tonic not as a beverage,” Mr. du Pont told an inquisitive reporter.

If you had the wherewithal, and many found they did, you could commission a one-of-a-kind, gem-encrusted work of art made by the master craftsmen at Tiffany and Co., and it’s a telling point that you’ll rarely find such workmanship and precious materials applied to water bottles and coffee thermoses.

The Drys Strike Back

“Anyone carrying liquor violates the law as much as one who carries a pistol.” —J.A. Leach, Head of NY State Prohibition Enforcement

During the early days of Prohibition, those charged with enforcing the new laws (and much less the public) weren’t sure what the legalities were in regards to the flask. Some locales enforced an outright ban, others didn’t, and some walked a sort of vague middle line, as pointed out by one newspaperman: “Officials have given out that it is all right to tote a flask if you aren’t caught. Obviously, as there is no penalty attached to any violation of the law, unless discovery ‘sets in.’”

Local ordinances aside, there were no specific penalties for flask-toting written into the Volstead Act because the Drys didn’t think they’d need them. They’d figured, in the spirit of trying new things, most Americans would stop drinking and therefore not need to carry around alcohol. And those who did not want to try new things, well, those booze-sodden degenerates would be easy enough to spot: they’d be staggering around with bottles of liquor tucked under their arms or perhaps even hillbilly-style jugs balanced on their shoulders.

Who would have guessed those devious bastards would adopt that old Victorian relic, the hip flask, and start sneaking them around under their clothing? And what Dry, in his worst nightmares, would have dreamed there would be so goddamn many of the sneaky bastards?

As often happens when self-righteous, this-is-for-your-own-good social movements stumble out of the gate, a wave of previously unimaginable authoritarianism was accompanied by a strong undercurrent of farce.

The government officially declared war on the flask in April 1921, stating with a straight face that flask-toting citizens were no different than those gun-toting gangsters who were presently shooting up the country. They began aggressively raiding clubs and arresting anyone carrying those dangerous containers. This was followed by the raiding and padlocking of restaurants and arresting waiters who dared serve set-ups (a cocktail minus the booze) to flask-equipped customers. Not surprisingly, the charges were thrown out of court by judges who felt funny about putting a fellow in jail for dispensing ginger ale and orange juice.

Indiana tried banning the sale of hip flasks (and cocktail shakers) entirely. Shortly thereafter, some very fashionable sterling-silver “cooking oil containers” and “milk shakers” appeared on store shelves.

Wading ever deeper into the sea of absurdity, the feds turned to spite. Since the government had already availed itself of the power to seize and auction off any vehicle carrying bootleg liquor, prohibition officials asserted they thus had the right to seize and sell men’s trousers found to be carrying flasks.

They had to lose a string of court cases before they abandoned this hysterical strategy.

A Menace to American Youth

A Menace to American Youth

“Jewelers Say Ma and Pa Buy More Than Flapper Daughters or Young Sons” —Headline, Evening Public Ledger, 1922

The Fourth Estate was willing to whip up a little hysteria of its own. There was a diabolically-charming fiend prowling the country, ravenous for the sweet flesh of the young, and its name was Hip Flask.

“Flask on Hip National Menace to Young,” shrilled a 1922 Evening World (NYC) headline. “The young man with the flask on his hip is the popular fellow,” the writer went on to complain. “His company is sought. The success of his party is assured.”

A breathless article in the New York Tribune claimed, “Little boys of 18 and 19 actually go to parties with flasks in their hip pockets and offer the contents to the girls, and some of the girls think it’s clever to take some.”

A well-reported congressional hearing wailed that the youth of America were fast becoming “hip-flask addicts.” Society matron and débutante-wrangler Mrs. William Laird Dunlop told the Washington Herald that “After the 18th Amendment, drinking became such a vogue that unless a young man came with a flask, he was not welcomed” at society shindigs.

That same year, W.E. Hill of the Chicago Tribune wrote of a typical debauched youth: “Lawrence, be it known, is, at the moment of speaking, tripping the light fantastic at the country club with a flask on his hip and a flapper for his partner who has been expelled from finishing school for having a still in her room.”

And perhaps a flask in her garter. If you fancied yourself a flapper, as many young women did during Prohibition, you understood that part of the uniform was a flask hidden somewhere on your person. Just in case Lawrence forgot his.

In 1924, Young Men Magazine took a different tack, blaming the evils of the flask on Prohibition itself: “The hip flask at public and private dances has become so common that it passes without comment. This is the ghastly heritage we are beginning to reap by believing that we can outrage constitutional law in this country with impunity.”

The Tide Turns

“When I’m elected we will not only reopen places these people have closed, but we’ll open 10,000 new ones. No copper will invade your home and fan your mattress for a hip flask.”— “Big” Bill Thompson, Future Mayor of Chicago

As Prohibition ground on, drinkers became more jaded about the Volstead Act and less respectful of the law in general. In the larger cities, celebrators began brandishing flasks in public, daring the cops to do something about it. It became a very overt way of saying, “Fuck you, Uncle Sam, and your stupid little law.”

The armchair psychiatrists on the Dry side immediately responded to this growing rebellion by hissing that flaskers were not so much personal liberty zealots as craven faddists driven more by bravado then any actual desire for legal alcohol. An editorial in The Christian Statesman put a finer point to it: “Perhaps they do not care so very much for drink, but consider it quite smart to startle others by their daring to do that which is forbidden by law. The hip-flask toters are of this class.”

When that sort of sniping failed to make a mark, the Drys rolled their well-used Howitzer of Hyperbole loaded with its mighty Cannonball of Equivocation: “The hip flask is no more a badge of honor than the dope gum or cocaine vial,” railed Reverend H.C. Newton. “All of them ‘radiate considerable good cheer’ to addicts and traffickers.”

See, you weren’t taking your flask to a bachelor party to liven things up, you were a junkie drug mule. In the tightly-wound mind of the prohibitionist, the sinister flask, that simple container designed to fit close to the body, had transformed into the strong right arm of Demon Booze itself.

Try as they might, the Drys couldn’t shame and demonize the flask out of existence. By the late 1920s, Johnnie Law had all but given up arresting citizens for carrying flasks. It was assumed that everyone was carrying one and you could hardly arrest everyone.

The 18th Amendment couldn’t kill the flask; indeed, it did quite the opposite. The harder the government chopped at the tree of booze, the more flasks sprouted up around it. It would take a return to sanity, namely the 20th Amendment, to halt the flask’s glorious ascension.

Post-Prohibition: The Soldier Puts Away His Rifle

“The flask is the alcoholic’s paintbrush.” —Andrew Jackson Jihad

The popularity of the flask immediately began to fade when it once again became legal to walk into a bar and procure legal liquor like a regular human being. The drought ended, the desert turned back to a lush paradise, and suddenly it didn’t seem necessary to lug around a canteen. Some learned to scorn the very sight of a flask, viewing it as an ugly reminder of an evil era best forgotten. A concomitant theory alleges American males became more “wussified” in the 1960s and no longer possessed the grit necessary to drink straight liquor served at body temperature.

The popularity of the flask immediately began to fade when it once again became legal to walk into a bar and procure legal liquor like a regular human being. The drought ended, the desert turned back to a lush paradise, and suddenly it didn’t seem necessary to lug around a canteen. Some learned to scorn the very sight of a flask, viewing it as an ugly reminder of an evil era best forgotten. A concomitant theory alleges American males became more “wussified” in the 1960s and no longer possessed the grit necessary to drink straight liquor served at body temperature.

Flasks remained popular with certain cliques, namely servicemen, bachelors and traveling salesmen. Private eyes and adventurers still used them, at least on the big screen, but by the 1980s—attacked by the twin specters of recreational drug use and MADD—flasks were locked in a cultural death spiral.

From then until now, flasks were gifts for groomsman, occasionally flashed on golf greens and sometimes found in the hands of artiste staking a stab at being eccentric. Hollywood hauls them out occasionally, either as an Instant Character Tell (“Oh my gosh, he carries alcohol around in a handsome silver container, thus he is a depraved alcoholic!”) or a Portable Mood Shifter (and apparently magical, as evidenced by two or more adults getting hammered on the contents of a single four-ounce flask.)

Because flasks are so rarely seen, they’ve taken on an exotic character. Produce one and, depending upon the nature of the crowd, people will gather around it like a campfire or slink off to a safe distance because you are obviously just trying to start some trouble.

All this said, flasks appear to have recently staged a small comeback. Judging by the army of custom flasks being sold on Etsy, hipsters have deemed them IN and by IN I mean Ironic/Nostalgic.

Other societal forces, namely the intense searches at stadiums and airports, have once again caused flasks to evolve to the point its hard to call them flasks. Foil pouches are being sold as “disposable hip flasks,” but surely that’s like calling the ubiquitous Red Plastic Cup a pint glass. Is a fake shampoo bottle (sold under the name Shambooze) designed to sneak liquor through airport security a flask or a repurposed shampoo bottle? Are the flask bra, crotch flask, and the beer belly flask really flasks or something that hasn’t been properly named yet?

A Flask for Every Purpose

“Quart—a unit of measure applied to the size of the hip-pocket in Kansas; a flask which holds about enough for five men in Boston, three in Ohio and one in Arkansas.” —Robert Jones Burdette

When Lucifer offers naive Prince Henry a drink from his “little flask,”* the prince wonders, “Will one draught suffice?” and Lucifer assures him, “If not, you can drink more.”

That fine wisdom only holds up, however, if you brought a large enough flask. The Devil plainly did, because when he pours some out for Hank, he assures, “Let not the quantity alarm you: You may drink all; it will not harm you.”

If you’re not out snaring royal souls, however, you may not need so much. While I tend to err on the side of excess, I recognize that you don’t take an elephant gun to a turkey shoot. Hoisting out a 48 ounce Texas Dinner Bell in a law office to celebrate a business contract may give your new investors pause. Contrarily, passing a two ounce Lil’ Nipper around a circle of football fans is likely to earn you the sort of reputation you don’t want.

You should have at least three flasks. One small enough to attach to a keychain, for emergencies; a four to eight-ounce mid-ranger for casual carry and a 10+ ouncer for when things get serious.

Before walking out your front door, size up the figural horizon: If it looks like fair weather, a Laddy Buck might be all you need. If you see a shitstorm brewing, you’re better lugging the Elephant Hunter.

If you have any sort of romantic streak, consider an antique. A widely varied and priced collection migrates through Ebay and other auction sites on a daily basis. In addition to the horde of Prohibition-era deco-streamlines, there’s a good representation of reptile-skinned Victorian hybrids, kooky trench-art wonders and a surprising number of interestingly inscribed military flasks.

There is something very fine about drinking from the exact same vessel as a 19th-century English scoundrel or a dashing Cossack cavalry officer. It adds a little flavor to whatever’s inside.

Try this: Hold a bottle of water in one hand and a flask filled with liquor in the other. Feel the contrast. It’s the same difference as holding a banana and a pistol. The flask and pistol both vibrate with a certain dangerous power.

That’s partly because it’s illegal to use both in most public places. The flask is lawfully considered an open container in the U.S., thus once brandished it is a misdemeanor. Just having it in a motor vehicle is illegal. Which, because of the vagaries of my psyche, makes flasks that much cooler to carry. Not to say I would be opposed to the issuing of concealed-carry permits for flasks, certainly an idea whose time has come.

I make a point—and so should you—of not using a flask in a bar willing to serve me liquor. It’s like walking around with an open umbrella on a perfect spring day. It makes you look affected.

After you’ve gotten into the habit of flasking, you’ll definitely want to encourage your friends to carry as well. Once you get the reputation as a flask man, they’ll start gathering around you like pigeons swarming old ladies with bags of bread. Which is fine the first dozen times, then it gets annoying.

I carry a flask because there are few moments in life that couldn’t stand a little more color. Or a lot more. Dull events are usually conspired by dull people and those are the sort who almost never condone—much less provide—alcohol.

Hence the flask.

*The Golden Legend (1851), a poem by William Longfellow.