Every man, whether he knows it or not, feels some primordial attraction for the allure of paradise.

After all, down the centuries the world’s major religions have been formed on some intangible paradise of another being promised as a reward for earthly toils. I grew up in a time when that notion of paradise became a pop culture phenomenon, manifesting itself in music, cocktails, fashion, and so on. Inspired by the recent statehood of Hawaii, man’s fancy turned toward a simpler time and place, one far removed from the stresses of modern life, the Cold War, and backyard fallout shelters. In the 1960s the phenomenon we call Exotica offered man a respite from modern living, if only for the time it took to play a Martin Denny record or sip a at a tiki bar. The reemergence of tiki culture in the 1990s serves basically the same function today as it did then, except today, people’s yearning for some long lost paradise is coupled with a desire for that long lost golden age when tiki bars studded the American landscape. For modern youth, the late 50s and early 60s represents that simpler time and place, an era that, perhaps, is their version of paradise lost. Many of today’s tiki hounds don’t actually have roots in that era, they grew up in the 70s and 80s. I grew up in the late 50s and 60s, and remember it all as though it were yesterday…

Growing up in Southern California tiki culture was inescapable: the backyard barbecues with fake waterfalls, tiki torches, tikis, and strings of brightly colored party lights shaped like the massive stone heads from Easter Island. Disneyland’s Enchanted Tiki Room, The Reef Lounge where one could dine on Polynesian cuisine while behind glass walls half- naked “mermaids” danced an underwater ballet, The Kona Kai, an upscale exotica eatery through which flowed an actual stream. The Bali Hai, an expensive spot on the San Diego bay with a thatched roof at whose center was a massive carving of a Polynesian man with bone through his nose. For a number of years, The Arthur Lyman Group was the house band.

It was a strange time. Exotica was everywhere. My favorite TV show was Hawaiian Eye, about a private investigation agency in Hawaii. Some of the on location shots were filmed in the International Marketplace where Martin Denny had made his mark. Arthur Lyman provided the music. I also loved Adventures in Paradise, about a tiki-wearing adventurer (played by Gardner McKay) who sailed his yacht, the Tiki, from one exotic port to another, getting involved in a new mystery each week. Ersatz paradise was everywhere. The early 1960s were a modern tiki hound’s wet dream.

There was a chain called Robert Hall that sold exotica wear for kids. Each pseudo Hawaiian shirt came with a tiki. The shirt I got was lime green and avocado with three-quarter length sleeves. The tiki had lime green rhinestones as eyes to match the shirt. When I wore this outfit to school, I felt like the hippest kid at Bancroft Elementary. As the years passed, the cultural landscape of America changed, and Exotica faded from prominence. I’d all but forgotten about it, until (in the latter part of the 70s) a bit of serendipity brought it back to me full force.

Two friends and I had traveled to Los Angeles to see a concert, and near the venue a strange apparition caught our eye. It was the legendary Hawaiian barbecue called Kelbo’s. The building looked wild. It was surrounded by tikis and tropical foliage. It had murals that dated back to the late 50s depicting native chiefs and topless maidens. Men were running toward the trees carrying naked women on their shoulders, while creatures seeming to be half ape, half man, chucked coconuts at one another. Could a mere dining experience truly live up to the kind of idyllic primitivism that these murals seemed to promise? We had to see. Inside Kelbo’s was more excessive still. The ceiling was festooned with puffer fish converted into lamps. Each had a different colored light inside, and emitted a soft eerie glow. The place was very dark, and as our eyes adjusted to the darkness it seemed that every square foot of space was filled with some garish trinket or display. On a bamboo platform behind the cashier there laid a mannequin in a diving suit stabbed in the chest with a knife. There was an entire wall made of lucite, and embedded in it where hundreds of doodads from 1963, the year the wall was made. It contained an irrational assortment of items, none of which seemed to bear any relation to the others: Barbie dolls, lipstick, guns, children’s toys, even two fried eggs. How any of this related to the theme of the restaurant I couldn’t figure then and still can’t. But it was stunning, and mind-boggling, and in a lurid pop art sort of way, beautiful.

The restaurant itself was like a jungle; a series of dark labyrinth-like passageways lined with enclosed booths.

The passageways seemed to snake around endlessly, and it seemed that a customer who left their booth in search of a restroom might never find his way back. The ceiling was covered with plastic foliage and fishing nets bearing various shells and starfish. The booths were like small grottos, and seemed like small self-contained total environments representing someone’s fever dream of what tropical paradise might be like. Each table had a kerosene lamp in the shape of a tiki. The tables had tops of thick resin embedded with shells, sea horses, gold coins, and so forth. You could order drinks with names like “The Skull and Bones”. They came in skull shaped mugs, and arrived at your table on fire. The drink menu had commentaries such as “this one’s Johnny Carson’s favorite!” or “this is the big artillery here, better watch out!” The napkins bore a drawing of a strange ape like creature holding a coconut and staring at a sign that read “IITYWIMWYBMAD”. When I asked the waitress what it meant, she retorted “If I tell you what it means will you buy me a drink?” I told her I would. And she told me that that was what it meant: it was an anagram for the phrase “If I tell you what it means will you buy me a drink?” Bar humor.

The Kelbo’s concept for what constitutes Hawaiian food was a simple one: just add pineapple to everything. Even the burger I had came with a slice of pineapple on it. The food was good, but the food didn’t really matter. What you were paying for was obviously the experience of spending an hour or so in a kind of anachronistic parallel universe a thousand miles removed from the modern world that existed just outside. We all realized that we’d stumbled on to something important. The hokey imagery of paradise-lost that at first seemed kitschy, started to seem like a really potent kind of symbolism. Being in Kelbo’s was actually like experiencing paradise. The fact that it was all false didn’t lessen its impact at all. It was evocative. It was like eating a meal at Disneyland. After that, my quest to seek and discover the last remaining vestiges of tiki culture began in earnest.

I dug out my old Martin Denny albums, which a few years earlier a biker friend of my father’s had turned me on to. He claimed it was the best music on earth and virtually forced me to sit down and listen to both sides of Exotica on headphones. He claimed it was the only music on Earth capable of bridging the generation gap because it was beautiful enough to appeal to older people, yet psychedelic enough to appeal to the young. I can still picture this hard-ass character extolling the virtues of exotic music. It’s an incongruous image, this guy with swastika tattoos holding this 50s record cover with Sandy Warner peering out from a bamboo curtain.

I dug out my old Martin Denny albums, which a few years earlier a biker friend of my father’s had turned me on to. He claimed it was the best music on earth and virtually forced me to sit down and listen to both sides of Exotica on headphones. He claimed it was the only music on Earth capable of bridging the generation gap because it was beautiful enough to appeal to older people, yet psychedelic enough to appeal to the young. I can still picture this hard-ass character extolling the virtues of exotic music. It’s an incongruous image, this guy with swastika tattoos holding this 50s record cover with Sandy Warner peering out from a bamboo curtain.

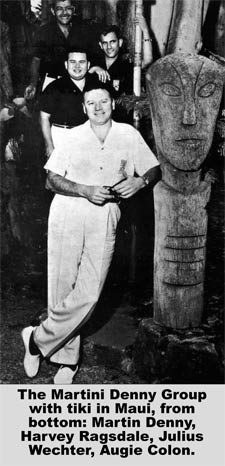

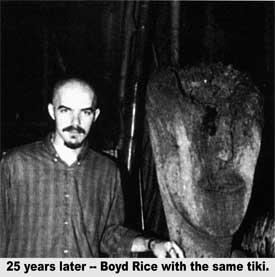

In those days every thrift store had multiple copies of Denny’s albums and in no time I had a few dozen. When a friend mentioned that Martin Denny was still playing on Kauai that was it: I was off to the islands on a pilgrimage to see the high holy man of Exotic Music. I went first to Honolulu, to visit what constituted the exotic music stations of the cross: Henry Kaisers Dome Theatre, the International Marketplace, the Shell Bar, Trader Vic’s and so on. The Shell Bar no longer existed, a victim of remodeling some 10 years prior. But at the International Marketplace I found the very tiki next to which the Martin Denny Group had posed on the back of Quiet Village. It was an odd tiki with an almost human head. There was one identical to it outside the Trader Vic’s in San Francisco. When I came back a year later, the tiki was no longer there.

I spent a few days soaking up paradise, drinking daiquiris at night on the beach at Waikiki as I listened on my Walkman to Annette singing her song Waikiki. But I was anxious to see Denny and so made off to Kauai. I walked into the room where Denny was playing at the Weilea Beach Hotel and it was pure magic. Martin Denny was brilliant. He was seated at a piano in one corner of a darkened room, and I ordered a drink that came in a hollowed out pineapple. This is the way to experience Martin Denny music — in a lavish Hawaiian hotel, sipping an exotic cocktail. It was definitely one of those peak experiences. The highlight of the evening came when Denny played Quiet Village. He had a switch on a tape recorder and the sound of squawking birds filled the room. Many of the tourists not familiar with Denny’s early work seemed a bit perplexed, and stared around the room in confusion, seeming to think that a flock of birds had somehow flown into the hotel and were now trapped in the lounge.

When Denny took his break I approached him with albums to sign, and gave him a copy of Throbbing Gristle’s Greatest Hits. It had just come out and had a mock Martin Denny cover and a dedication to him as well. He was excited that young people were still inspired by work he’d done 20 years ago. I made arrangements to come back when he got off and conduct an interview. I came back later, caught the end of his set, and we stood in the lobby talking until nearly four in the morning (this despite the fact that he had to rise early for an important appointment that morning). For Denny, the idea of paradise was not just an empty concept, it was a way of life. He lived it. He spent his days on the beach and the golf course, and spent his evenings playing piano. He was clearly a man who was getting exactly what he wanted out of life.

Denny was aware of the irony that his music is intrinsically associated with Hawaii, yet isn’t the least bit Hawaiian per se. Hawaiian music is steel guitars. His music is piano based with vibes. And yet, by creating a lush ambience that’s evocative of paradise, it’s perhaps truer to the spirit of Hawaii than anything ever done on steel guitar. Over the years Denny’s met thousands of visitors to Hawaii that informed him they’d wanted to visit ever since first hearing his music. If he had a small percentage of the business he’s generated for the islands he’d be a very rich man indeed.

Back on the mainland, any travelling I did became a pretext for my on-going tiki bar pilgrimage. I was amazed by the sheer amount of variation that seemed to exist from one to the next. The degree of excess and extravagance seemed over the top in even the most subdued tiki bar. They were seldom disappointing, and even the most tasteful examples seemed possessed of a garishness and romance seldom found in modern life. They all seemed to embody the spirit of another time, even if not another place. I criss-crossed the western United States, and at the time nearly everyplace had some vestige of tiki culture. Phoenix, Arizona even had a tiki motel, called the Kon Tiki. Its slogan was “a little bit of Honolulu in Phoenix”. Except for the heat and humidity, Honolulu and Phoenix couldn’t be more dissimilar; and the motel looked like it had been plucked from Maui and unceremoniously deposited in the desert.

In a thrift store I saw a tiki mug marked “Harvey’s Sneaky Tiki, Lake Tahoe”. The mug looked to be from the 1950s, and I assumed the place must long since have vanished. But when visiting Tahoe I was pleasantly surprised to find that it still existed, on the top floor of Harvey’s Hotel and Casino. And it looked as if it must not have changed in 20 years.

In a thrift store I saw a tiki mug marked “Harvey’s Sneaky Tiki, Lake Tahoe”. The mug looked to be from the 1950s, and I assumed the place must long since have vanished. But when visiting Tahoe I was pleasantly surprised to find that it still existed, on the top floor of Harvey’s Hotel and Casino. And it looked as if it must not have changed in 20 years.

In nearby Reno I discovered a place called Trader Nick’s that was much smaller, but equally lavish. A lot of bars tried to cash in on the success of Trader Vic’s, a name that had become synonymous with tiki bars, that every one sounding somewhat similar could communicate to someone hearing it for the first time exactly the sort of exotic ambiance they could expect. So I’ve been to Trader Nick’s, Trader Mick’s, and Trader Dick’s. Going down the Pacific Coast Highway I spotted an ancient looking sign for a place called Trader Ric’s. The huge tiki on the sign looked so faded that I doubted the place even still existed but at the outskirts of Pismo Beach, I spotted the place: there were tikis and a catamaran out front. The lot was empty, but I drove in anyway. Miraculously, it was open. The main dining room overlooked the ocean, and as you ate you could watch the waves crashing against the rocks on the cliff below. There were no other customers and the atmosphere was ghostly. It genuinely seemed as though I had walked into a scene from another time, a remnant of a past world. The world of which it was once a part no longer existed, and it seemed that it, in fact, couldn’t much longer survive in this world. I felt a sense of melancholy, and a heightened awareness that I was experiencing one of the vestigial remains of a phenomenon whose day had come and gone, and now even this last bastion of that would soon vanish too. I was sad. I knew only too well that I’m usually correct about these things, and it didn’t take terribly long to see my worst fears were well founded. A few girls and I went to the Reef Lounge to check out the topless mermaids and found it had closed a few months before. A friend went to visit a tiki palace he’d often viewed from a train, and arrived just in time to see the building being demolished. One after another, the places began to vanish. Trader Vic’s closed its San Francisco location after something like 30 years at its Casino Alley location. Kelbo’s lasted until the 1990s, but finally shut its doors to make way for a strip club.

But while the bad news is that a lot of the best places are nothing but a memory, the good news is that one of the very best of the tiki bars has managed to survive and prosper. It’s San Francisco’s Tonga Room at the Fairmont Hotel. The Tonga Room began its life as the Fairmont indoor swimming pool. When the tiki craze hit the management decided to turn the space into an exotica themed lounge, scattering the pool’s bottom with various shells and starfish, thereby converting it into a sort of ersatz lagoon. They surrounded two sides of the pool with thatched roofs for patrons to drink and dine beneath, and painted the ceiling black so as to give the illusion of being out of doors under a night sky. And the final touch was sure genius: they installed an elaborate sprinkler system above it all to replicate the experience of a tropical downpour. That’s right, every 20 minutes or so the restaurant is filled with the sounds of tape recorded thunder, there are flashes that appear to be lightning, and then streams of fake rain pummel the pool for 60 seconds or so. It’s a low-tech spectacle that never fails to enchant even the most jaded viewer. At a certain time of evening a small boat containing a live band floats out into the center of the lagoon and plays for the remainder of the evening. The Tonga Room may well be the last bastion of a once booming phenomenon that remains more or less intact. If it is one of the few remaining vestiges of what Exotica was at its apex, we can at least take some joy in the fact that it’s also one of the best manifestations of the trend.

William Butler Yeats once said that there was something essential in the nature of man which caused him to feel some deep affinity with (or yearning for) another time or place, whether real or imagined. In the 60s, Exotica was a large scale manifestation of that impulse. And the remembrance of that bygone era today, is no doubt only the most recent incarnation of that same timeless impulse.

–Boyd Rice

(Boyd Rice has performed and recorded under the name NON since the mid 1970s. He is co-author of Re/Search’s Incredibly Strange Films. He currently resides in Denver, Colorado.)