Of the many things Russians are famous for, first and foremost is their monumental appetite for booze.

They approach the act of drinking with breathtaking zeal, with a single-mindedness born of centuries of internal conflict and rank political repression. Not to mention the weather. It’s fucking cold there.

And contrary to most Western countries, the Russians do not see massive inebriation as something excessive or questionable. It is merely Russian.

Drinking as the Russians Do

Like many of us around the planet, Slavs drink to have fun, which means they drink to get drunk. And it’s important that the booze-up have a point, a reason. Big events, like holidays, birthdays and anniversaries, are obvious occasions for a good bender, but pretty much any excuse will do. It is this need for a reason to drink that gave rise to one of Russia’s oldest toasts: “May we always have a reason for a party!”

Drinking to honor guests in one’s home is a fading but still prevalent tradition amongst the Russians. Failing to offer a guest an intoxicating beverage was considered a grave insult. Likewise, a guest who refused the offered tipple, or failed to become thoroughly pie-eyed by the end of the evening, had insulted his or her host. Tales have come down of visitors actually pretending to be thoroughly loaded so as not to offend. As a show of respect, hosts poured drinks for everyone at the party, even those enduring a bout of abstinence. Visitors who arrived late to a party were expected to drink a “penal,” or a full glass of whatever it was the host was pouring. And when it was time to go home, custom maintained that the guest knock back one last round. Among Westerners, this is known as “having one for the road.” Russians call it na pososhok, which, loosely translated, means “Good luck on the road,” or “Lucky travels.”

Russian drinking culture was (and is) flush with other time-honored dos and don’ts. One of my personal faves is when a drinker opens a bottle of hooch he is expected to drink it all. Drinkers are aided in this lovely venture by the time-honored belief that if a glass still had booze in it, even a dribble of luke-warm backwash, it is not to leave its owner’s hand. It is fine, however, to set an empty glass aside, especially if you wanted a refill, since it was frowned upon to fill a glass while someone is holding it.

Toasting is a big deal, too. Only rarely was a drink consumed without the accompaniment of a few well-chosen words of good cheer and a clink of glasses. (In fact, about the only situation where toasting is forbidden is at a wake, where solemnity is, of course, key and tapping glasses is considered crass.) Once a toast has been voiced in someone’s honor, drinkers who participated in the toast are expected to drink their glass dry as a show of respect to the toastee.

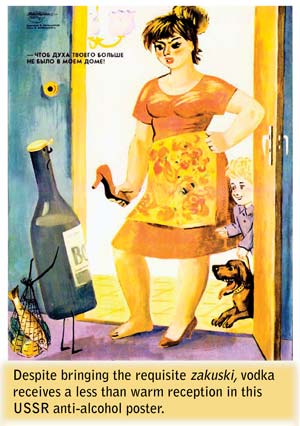

Each drink consumed on a Russian bender is almost always consumed in the company of food, be it a full meal or a simple platter of hors d’ oeuvres known as zakuski (“little bites”). Zakuski runs the gamut from things as basic as a pickle or sliced beef on black bread, to such expensive extravagances as beluga caviar. After each drink (don’t forget the toast!) everyone enjoys a bite of zakuski, which served the dual purpose of cleansing a reveler’s palate, while simultaneously preventing him from getting too loaded too soon which is considered bad form.

The Silent Spirit

Russians and vodka are nearly inseparable in the global consciousness. It is impossible to talk about getting ripped with the Russians without a detailed look at that beautiful and sexy white liquid. Crystal clear, all but odorless, and gentle on the taste buds (all reasons for its sobriquet “the silent spirit”), vodka is cock of the hard liquor walk, at least as far as consumption is concerned. It’s the best-selling spirit on Earth, and continues to reinvent itself with new flavors that inspire hundreds of new cocktails every year. To say that pretty much anyone who has partaken of alcohol has at least a passing familiarity with vodka is to state nothing but a flat fact.

Even though it wouldn’t be called “vodka” until the 1600s, the liquor has an ancient lineage. It evolved from aqua vitae, or “water of life,” the primordial booze-soup which so many tipples call Papa. Over the centuries, it went by “bread water;” “korchma wine;” “burning wine;” and “bitter wine;” and way back in the day folks called it simply “drink.”

Vodka and the State

Because vodka is so simple to make, in the past many Russian villagers have made their own. Urbanites too busy to tend a still were supplied by a vast army of distilleries which popped up in towns and cities. Everyone had easy access to as much as they wanted. That being the case, it should come as no surprise that those who wanted to drink it (the people) came into conflict with those who wanted to control it (the government) and that vodka became a central aspect of Russia’s seemingly endless rounds of civil strife.

Back in the mid-1540s, Tsar Ivan the Terrible (who was as crazy as a shit-house rat), cast a sad eye at his empty coffers and decided that something had to be done. His solution was to install a state monopoly on vodka production, as well as all other intoxicating drinks. At the same time, he opened Russia’s first vodka bars (kabaks), which were also controlled by the state. He demanded perfection and routinely murdered distillery workers who failed to pass muster. He also sicced his troops on any citizen brazen enough to erect a personal still. On the sunny side, historians have argued that Ivan’s brutal control over the vodka business led to an exceptional bottle of booze.

Things muddled along with little change for the next couple of centuries, until, in 1716, Peter the Great got involved. Pete had the foresight to see that loosening the government’s grip on vodka production would benefit the average Russian and the state. He reformed the laws governing sales and production, making it possible for any average Boris to make and sell vodka—provided, of course, that Boris purchased the requisite license from the government. This licensing scheme led to an eruption of vodka factories, and people with the right business acumen (and connections) became quite wealthy.

It is worth noting that Peter the Great was a serious boozehound. He began the day with vodka and ended it with vodka, with pauses in between for vodka. It is said that he consumed several liters of the stuff every day, making him quite the Party Tyrant. He even had a special mug made, which held 1.5 liters of vodka, that he would foist upon visiting diplomats, forcing them to down the whole thing. It was Peter’s way of testing whether or not he could trust a foreign dignitary.

Most of Peter’s progress was sadly erased with the ascension of Empress Catherine the Second. In addition to enjoying the ministrations of several hundred lovers over her lifetime, Catherine believed that the only truly worthy people were the noble-born. Proceeding accordingly, she revoked all state licenses from the merchant class and handed vodka production, in its entirety, to the aristocracy. Like Ivan before her, Cathy cracked down on those who broke the rules, generally by confiscating their property and introducing them to the pointy end of a cavalry cutlass. Few citizens lost any sleep when the creepy old nymphomaniac croaked of a stroke in 1796.

Early in the nineteenth century, proprietors of Russia’s numerous vodka taverns staged a small revolt, after which they, and their fellows of the merchant class, regained a little of their former freedom. And it might have continued going well for them, if not for the arrival on the world stage of a pint-sized, wannabe-world-conqueror from Corsica named Napoleon Bonaparte. His desire to forge a French empire led to France, which he had taken over in a coup d’état, going to war with England and Russia. Russia was financially unprepared to resist Bonaparte’s invasion and set about raising money any way it could, starting with imposing yet another state monopoly over the vodka industry.

Early in the nineteenth century, proprietors of Russia’s numerous vodka taverns staged a small revolt, after which they, and their fellows of the merchant class, regained a little of their former freedom. And it might have continued going well for them, if not for the arrival on the world stage of a pint-sized, wannabe-world-conqueror from Corsica named Napoleon Bonaparte. His desire to forge a French empire led to France, which he had taken over in a coup d’état, going to war with England and Russia. Russia was financially unprepared to resist Bonaparte’s invasion and set about raising money any way it could, starting with imposing yet another state monopoly over the vodka industry.

Bonaparte eventually got his hash settled in 1815, but nothing really improved for Russia’s vodka enthusiasts. And before the century was out, their lives would begin to turn toward the surreal.

In 1894, a chemist called Mendeleev arrived at the perfect (according to some mysterious criteria) mix of pure vodka and water. His conclusions met with approval from the Powers that Be, and new regulations were born, resulting in a bottle of booze with a lot less horsepower than had previously been the case. The government used Mendeleev’s findings to grab an even stronger hold on the industry than ever before. And if all that wasn’t bad enough, Russia went to war again in 1904, this time with Imperial Japan. During the conflict, the government, for reasons they never adequately explained, instituted Russia’s first national Prohibition laws. Vodka bars now had strict hours of operation, and no vodka was to be sold after eight at night or before ten in the morning. In general, vodka became more difficult to come by. Some historians argue that its new scarcity led to a decrease in alcoholism, but that’s the same as saying that a sudden dearth of oxygen will lead to a drop in overall breathing.

Then, in 1917, everything went completely down the shitter. After a series of mini revolutions, the Red Army, under the control of Vladimir Lenin, wrested control of the country from the Tsarist oligarchy and installed the Bolshevik (Communist) government.

Now, one of the central tenets of Marxist ideology is the idea that in order for the workers to rise up and cast aside the repressive shackles of history they need a sort of master intellectual to guide them along the way. On that score, Lenin and his cronies were in full agreement with Marx (who, by the way, had numerous servants, the big hypocrite), and one of the things they decided the workers could well do without was vodka. The outgoing Czarist government had held near total control of the national beverage, and the Bolsheviks couldn’t think of any good reason to relinquish it. In fact, they decided to take things a step further, first by banning any and all private ownership of vodka distillation, and then condemning drunkenness as a “social evil irreconcilable with the proletarian ideology.”

Those few lucky souls who had, up to that point, managed to keep their operations free from the tentacles of government suddenly found that their luck had run out. Many were condemned as enemies of the state, including a pair of brothers named Vladimir and Nicholai Smirnov. Nicholai was executed in a Ukrainian gulag, and even though Vladimir escaped with is life, he died penniless in France less than 20 years later. The Bolsheviks added the sad and final exclamation point to the tale when they turned the Smirnov distillery into a parking garage.

Those few lucky souls who had, up to that point, managed to keep their operations free from the tentacles of government suddenly found that their luck had run out. Many were condemned as enemies of the state, including a pair of brothers named Vladimir and Nicholai Smirnov. Nicholai was executed in a Ukrainian gulag, and even though Vladimir escaped with is life, he died penniless in France less than 20 years later. The Bolsheviks added the sad and final exclamation point to the tale when they turned the Smirnov distillery into a parking garage.

Worker dissatisfaction grew, first in metropolitan centers, then spreading swiftly to the hinterlands. Under Communism, wages had plummeted, housing was scarce, food shortages were epidemic, and anyone who complained got disappeared to Siberia. Vodka was pricey, if you could even find any, and just how in the hell were they supposed to keep going if estranged from the loving arms of Mamma Vodka? Soon enough, the proletariat decided that even if they might eventually learn to muddle through without her soothing caress, they were damned if they would.

“No Drink, No Work,” became the rallying cry of a populace who had had more than their fill of that but-it’s-for-your-own-good bullshit. The state ignored them for as long as they could, but eventually put it together that unless the proles were placated, the newly-minted Workers Utopia would crumble like a week-old blini. So, in 1924, the government lifted many of its vodka regulations.

As it turned out, Communist business and social strategies gradually proved themselves so ineffective that the average worker’s lot improved very little. But at least they could get smashed.

Flash forward to the 1980s and the rise to power of Mikhail “What the Hell Is This Thing on My Head?” Gorbachev and a bunch of new-fangled policies called perestroika. Gorby understood that the Soviet Union had become a sort of sociopolitical chemical fire that could no longer sustain itself. His plans called for a wholesale reinvention of Soviet culture. But, because governments—any and all governments—are pathetically unable to learn from the past, Gorby’s scheme included an ill-conceived “war on drunkenness.” He too felt that drunkenness didn’t mesh with Soviet philosophy, and pushed policies such as revoking the driver’s licenses of those convicted of public intoxication and dramatically raising the price of vodka.

When he completed his odious design, a single bottle of vodka cost over 5% of an average worker’s monthly salary, and even if they had the cash, thirsty folks had to wait in three-hour lines to make a purchase. As vodka became harder to come by, so too did mouthwash, cologne, cough syrup or anything else whose primary ingredient was alcohol. The people were not pleased, and one disgruntled fellow took his complaints straight to Gorbachev while he was out and about pressing the flesh. Gorby listened, shrugged, and told the guy that vodka wasn’t a necessity. Then he raised the price again. Is it any wonder that only a few years later the once great USSR took one last rattling breath and died?

When he completed his odious design, a single bottle of vodka cost over 5% of an average worker’s monthly salary, and even if they had the cash, thirsty folks had to wait in three-hour lines to make a purchase. As vodka became harder to come by, so too did mouthwash, cologne, cough syrup or anything else whose primary ingredient was alcohol. The people were not pleased, and one disgruntled fellow took his complaints straight to Gorbachev while he was out and about pressing the flesh. Gorby listened, shrugged, and told the guy that vodka wasn’t a necessity. Then he raised the price again. Is it any wonder that only a few years later the once great USSR took one last rattling breath and died?

In truth, the collapse of the Soviet Union proved to be a boon for Russia’s vodka industry. In 1990, Russia elected a straight-up, unabashed drunkard as its first president, and Boris Yeltsin soon issued a decree abolishing the state’s vodka monopoly. Private distilleries, many of them bearing ancient names, sprung up almost overnight, and a whole raft of Russian vodkas suddenly flooded the international market, nowhere more so than in America, where the silent spirit far out-sells any other distilled spirit.

Enter Vladimir Putin. The former KGB agent, elected president in 2000, was known to have a taste for the finer things—the best clothes, the best food, the best vodka. Shortly after his election, he began grousing about the glut of inferior vodkas on Russian shelves. They sullied the reputation and traditions of the national beverage (not to mention the fact that vodka was a vital part of the country’s economic infrastructure) and he wanted something done about it. So what did he do?

You guessed it. He nationalized the vodka industry.

A Final Note

I’ve had the opportunity to tie one on with many of my fellow Russian inebriates. From those experiences I have taken this: no matter what’s going on politically in their country, and no matter the highs and lows of their personal circumstances, Russians remain some of this planet’s leading booze appreciators. If you’ve never had the pleasure, I suggest finding yourself some Russian drinking companions post-haste. Doesn’t matter if you know them or not. You’ll be friends by the end of the night.

(Note: The Author is indebted to the following: Ian Gately; Ian Lendler; Barbara Hollander; A.J. Baime; Stuart Walton; Joseph Lanza; David Wondrich; Nicholas O. Warner; W.J. Rorabaugh; Eric Burns; Edward Behr and Daniel Okrent.)