When I mentioned to a stranger that this magazine was about to celebrate its tenth year in publication, he reacted with violent dismay.

“Ten years?” he bellowed. “How the hell could they have stayed alive for so goddamn long?”

It was a fair question. I wasn’t certain if he was referring to the health of the staff or the magazine’s longevity, but in the end they are the same. I have worked for a number of publications in my day, but this was the first that exacted a definite physical toll—like working in a coal mine.

When I admitted to the man I’d been on board since the first issue, I vaguely felt as if I were confessing to a minor yet sordid crime. He leaned away from me a bit and said, “Well, you must have some weird stories to tell. If you can remember any at all.”

Indeed. What does the coal miner remember from toiling ten years in the black underbelly of the earth? What sticks in the mind? Not the labor, certainly; more likely the times when the canary gave a squawk and keeled over, or when the roof quaked and buckled and the elevator seemed a million miles away.

But those are not my stories to tell. I admit without the slightest amount of guilt that I did my best to stay out of the mine. Aside from an occasional visit, I preferred to observe from a safe distance. To get the real inside view, we must turn to the lunatic whose idea it was to dig that hole in the first place: the founder, editor and publisher of Modern Drunkard Magazine, Frank Kelly Rich.

–Giles Humbert III

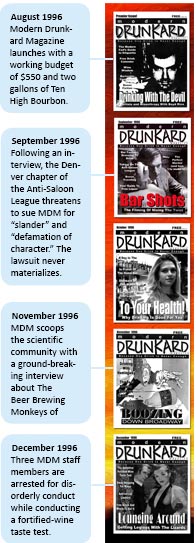

What must have possessed you to think you could get away with publishing something called Modern Drunkard Magazine?

If I remember correctly, it was Jim Beam. I was drunk in a bar, and it struck me that alcohol had become society’s whipping boy. An army of special interest groups were beating their sins into it, and very few were standing up in its defense. Alcohol has been with us since we started calling ourselves human, through floods and famine, war and peace, our constant loyal companion, and now a smug gang was laying into it like it was some filthy stranger who’d crept into their bedroom while they were sleeping. I wanted to get into the trenches and defend it. I wanted to celebrate it.

And what made you feel you were qualified to publish such a thing?

And what made you feel you were qualified to publish such a thing?

Technically, I had no qualifications whatsoever. I’d never worked at a magazine, never studied the field in college, I didn’t even bother to read a book about the subject. What I did have was a certain amount of experience in the field of alcohol. I’d spent the previous ten years reeling around Europe and America, immersing myself in the drinking culture.

By that I imagine you mean getting drunk in a variety of bars.

Yes.

Why did you choose to launch the magazine in Denver?

It seemed like the right place. We became acquainted while I was randomly driving around the country in a ‘67 Corvair. On the way out of town I saw this incredible retro sign for a dive bar called the Lion’s Lair. I stopped in for a drink, and I quickly determined it was the finest dive bar on the planet. I drank there all night and slept in my car. In the morning, after bracing myself with a handful of Bloody Marys, I walked in concentric circles until I found a place for rent. I had a four-book contract at the time, and I wrote most of the third book in one of the bar’s booths.

So, when you decided to launch the magazine, I imagine you solicited investors, recruited an experienced staff, leased a fancy office, and—

It was a tad more guerilla than that. I managed to hold back $550 from the bars, which translated into 1,000 issues from a cut-rate printer. The office was my apartment, the staff was my girlfriend and a roommate. And you.

When I first met you and the rest, I thought you were a gang of hobos.

We didn’t want to be hobos. We wanted to drink and dress like David Niven or the Rat Pack. But somehow we always ended up looking and lushing like Charles Bukowski. Money was tight.

I remember those rumpled thrift-store suits you chaps liked to wear.

We all grew up below the poverty line. Rich kids dress down, poor kids dress up.

The first issue was—

Hideous. An actual monstrosity. The printer—I recall he was a religious nut of some sort—didn’t know what he was doing and neither did I. It looked worse than an anarchist zine run off on a photocopier. We had three real ads and a gang of fake ones I made up.

How was it received?

The drunks down at the bar seemed to like the idea, if not the execution. I was surprised to discover that some people didn’t think drunks deserved a voice, that drinking was something shameful and not to be celebrated and defended in print. Naysayers abounded. Most of the local publications of the day reckoned we were some kind of one-off joke. Some of them still refer to us as a “zine.” Even when we were a zine, I hated that tag. I know punk publications think it’s a badge of honor, but I always thought the term was dismissive.

And the Drunkard has outlived nearly all of those publications.

Sweet, sweet vengeance. I wish I could say I was big enough not to savor their deaths, but I wasn’t.

Describe a typical day at the office.

Utter chaos, as you might remember. To quote the late, great Dr. Hunter S. Thompson, we were “like a gang of junkies trying to send a rocket to the moon to check out rumors that the craters were full of smack.” Substitute “junkies” with “drunks” and “smack” with “booze” and it very nearly perfectly describes the first year. I believed very deeply in what I was doing, but I didn’t know what the hell I was doing, if you know what I mean. I didn’t know what the rules were, so I had no qualms about breaking them. We were completely out of control. We were worse than wild monkeys.

>

Yet you managed to put out issues.

Always by the skin of our teeth. The first three weeks of the month we’d spend in the bars, doing our research. It’s one of the best things about the gig—you can go out and get utterly out of your mind, yet you are technically on the job. Then, I’d snap out of it and realize we had a week to turn the fucker in. The last week was always a raving, fear-induced frenzy. Promises would have been made to advertisers and the printer, and back then I took those deadlines very seriously. I’d go without sleep for days on end, cranked up on caffeine, bourbon and hillbilly music, trying to get the bastard finished. As soon as I turned it in, I’d swear to God in Heaven that I’d dive right into the next issue. But it never worked out that way. I’d always end up back at the bar, refilling the well, as it were.

So it was much as it is now?

When you’re right, you’re right, and you’re right.

How did the magazine manage to survive?

Hook and crook. A lot of bounced checks, a lot of evictions, a lot of burned bridges. Constant fear and terrible lies. We lived on the three Rs: rotgut, ramen and regret. I was so wrapped up in the sheer idealism of the venture, that I figured the end would more than justify the means. But it was also a thrilling time because we found great pleasure in how politically incorrect we were. I would sit on a bar stool and tremble with joy at how many snooty craws we were stuck in. I’ve always had a rebellious streak, I love the idea of kicking against the smug pricks who say what the rules are supposed to be and how you’re supposed to behave.

You always seemed to have money enough to get drunk, if I remember right.

Well, that was our main priority. The way I figured it, if I wasn’t out there doing the research, the magazine would ring false. If I was going to write about fortified wine and two-week benders, then, by God, I had to drink that swill and stay drunk two weeks. All the writers I admired actually lived the stories they wrote—Hemingway, Bukowski and Thompson—so it seemed essential that I do the same. We got plenty of support, a lot of bartenders fronted drinks, and well-wishers brought by bottles. A sympathetic microbrewery gave us as much keg beer as we wanted, so there was always a warm keg of beer squatting in the middle of the living room. It drew a crowd. I would wake up in the afternoon and it would be as if someone had detonated a beer bomb. People, strangers mostly, would be strewn about like broken dolls. It’s amazing anything ever got done.

Did you ever get the feeling what you were doing was somehow immoral and reprehensible?

The idea visited me upon occasion. A lyric by The Damned sometimes came to mind: “I’m on the side of the angels, but the Devil’s my best friend.” But I never really believed it. I’ve always considered booze as something kind and pure. I felt more like a paladin than a force of evil. If people think alcohol is evil, they should visit the Middle East and see how prohibition is working out over there.

Did you ever have an intimation that things might eventually collapse?

You couldn’t help but have suspicions. After we got into the groove, if you can call it that, I knew we wouldn’t be able to sustain that lifestyle for long. The whole thing was geared toward immediate survival; very little thought was dedicated to what might happen tomorrow. I started feeling more than a little akin to that utterly insane conquistador Aguirre going up the Amazon in search of El Dorado. The journey starts with the noblest of intentions, but after a while the haunting knowledge sets in that the ramshackle and rudderless raft you’re riding is heading for a waterfall. Finally you turn a bend and you see it coming, and you feel helpless to do anything about it. The crew was steadily going insane, and the captain was already there. It came to the point that every afternoon I would wake up and wonder, Good God, how much longer can this go on? Doom was certain and when it came it was almost a relief.

After nine issues in one year, the magazine folded.

We found our waterfall, all right. I’d broken up with my girlfriend, credit card companies were howling for my blood, I was physically unsound, and had just been evicted for the third time. It seemed like an excellent time to crawl out into the weeds as far as I could and try to screw my head back on. I remember packing up my Corvair. Everything I owned fit in the trunk. Everything else had been ground up by the big adventure.

Any regrets?

Not really. I had a very powerful knowledge that mistakes had been made, but that’s all part of the trip. The good times far outweighed the bad. Regardless of the aftermath, it was one of those adventures you can never regret. As long as you believe the war is just, you never regret picking up a gun, regardless of whether you come home victorious or defeated.

What happened next?

I moved into a basement apartment, got a job writing scripts for used-car commercials, and moonlighted as a bouncer at a dive bar.

And shot a film.

Right. I wrote and directed a no-budget 16mm black-and-white booze noir called Nixing the Twist. It concerned an All-American boozehead working for the Russian mob. Helluva a lot of drinking in the movie, naturally. On the screen and on the set. We had a local premiere, but it never went anywhere.

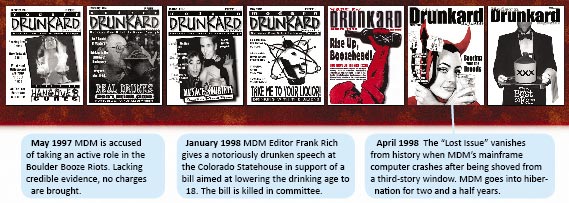

You managed to find time to give a rather notorious speech at the Colorado Statehouse.

Ron Tupa, an enlightened state representative from Boulder, had an idea about lowering the drinking age to 18. It was right after the Boulder Booze Riots. The kids wanted booze and he meant to give it to them. He enlisted me to give a speech about how Prohibition had failed 50 years before and why it would fail again.

Did you set them straight?

Oh, hell no. I stayed up all night in a red-wine frenzy, hammering the speech together, then stopped at a bar on the way. I have a hard time getting in front a crowd sober. Things got out of hand. I meant to sound like the sonorous voice of reason, but, according to a friend who’d tagged along, I came off like Mussolini on acid.

Then, roughly a year after your trip over the waterfall, you published another issue.

Then promptly folded. It was supposed to be the great comeback issue. I’d managed to forget all the insanity and horror and just remembered the good times and that fine sense of purpose. I remember calling you and asking you to return from England and you laughed at me and called me a fool. Told me to get next to God.

It was sound advice. How did you manage to sink this particular raft so quickly?

I had some help. The first issue went over well and I was about to turn in the second when tragedy struck.

In the form of an ex-girlfriend.

Right. Not the one who had been with me at the start, but a later version. She came by, we got into an argument, she left, I went to the bar for a drink, she came back and shoved my computer out of a three-story window. She later told me it was just trying to escape, but I didn’t believe it. I had no back-up, of course. I didn’t think in those terms.

How’d you take it?

After inspecting the smashed hard drive, I went back to the bar and drank. Force majeure. It was demoralizing, but nothing could be done about it.

It took you another year and a half to relaunch the magazine for the third time. Why so long?

I got wrapped up in things. I managed a restaurant, drank a lot, and just drifted along. In a way it was pleasant just being another drunk at the bar having a good time without feeling the need to write about it. The unexamined life may not be worth living, but it’s an easy life. In the back of my mind, however, I knew I’d make one more go of it. I’d head up the river one more time. And this time it would be different.

Would it, now?

For sure. I took things a little more seriously. Before I’d always gotten on the boat with a certain amount of fatalism, with the knowledge that it would capsize sooner than later. It was a straight Quixote trip. This time I meant to make it all the way down the river. When I first got into the game I was naive and perhaps even innocent in a twisted sense of the word. It was like working on something while underwater and in complete darkness. This time I’d have a torch of experience to light the way.

Torches don’t work well underwater.

And don’t I know it. The main lesson I brought back was never get off the boat.

You got a new staff together.

Right. First I suckered you and the Concerned Cad into coming back. I gathered the rest of the staff from my friends—you meet a lot of talented people in bars. My wife Christa took over marketing. Troy, Luke, Dave and Jimmy came on as salesmen and writers. Since then the staff has steadily expanded.

Was cutting down on your drinking part of the New Way?

No. I imagined that the aggressive drinking thing was part of the problem in the early days, but I’ve proven myself wrong. The problem was my attitude. I’ve experimented with not drinking on the job, and it really, really sucks. Why should we have to wait until after work to have a good time?

Why did you decide to start having conventions?

Members of our website’s chat board wanted to drink with each other in person. It seemed like a damned fine idea. It’s a way of uniting the tribe. It’s the first step toward making waves politically.

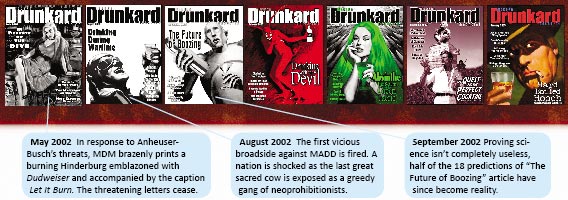

The magazine took on a much more pronounced political bent this time around.

True. The world had gotten much darker for drunks during the interlude. MADD was running amok to the point even the dethroned founder called them rabid teetotalitarians. Aside from a few web sites, no one seemed willing to call them out. Furthermore, the pharmaceutical companies, fronted by the medical community, had launched a coordinated campaign designed to demonize alcohol.

Did they, now?

Yes. With the government’s help they’re attempting to replace alcohol with their drugs. Look at the ads for Zoloft; the symptoms it’s supposed to suppress are the very things that alcohol has been so effective in dealing with for centuries—shyness, stress, etc. The difference being, alcohol also packs a powerful socializing effect. When you go to happy hour to unwind after work, you socialize with fellow humans. You are reminded you are part of a larger society. But who gets together to pop Zoloft? Who feels inspired after taking Zoloft? They want you to pop your pills, zone out in front of your TV, go to sleep, go to work, consume and die. That’s not a human life. That’s the life of a robot.

They’re trying to turn us into robots?

Yes. The Terminator series aside, robots don’t get into much trouble. Drinkers occasionally will. I hate to sound like a conspiracy theorist, but check this out: The most powerful anti-alcohol organization on the planet is the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. They have a $9 billion war chest and annually dole out millions of dollars to many if not most of the active neoprohibitionist organizations. And get this—it was created by one of the founders of Johnson & Johnson, one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical conglomerates. Coincidence? Maybe, but I doubt it.

Do you intend to keep moving in that direction?

Absolutely. It’s not enough to just rail against the neoprohibitionism that’s coming down the pike. We have to start organizing protests, we have to start putting people in the streets and ballots in the box. Politicians don’t take drunks seriously, and they shouldn’t, because we’re not organized. We’re going to try to change that. They have to realize that if they’re going to chip away at our right to drink, they’re going to have to pay a price on election day.

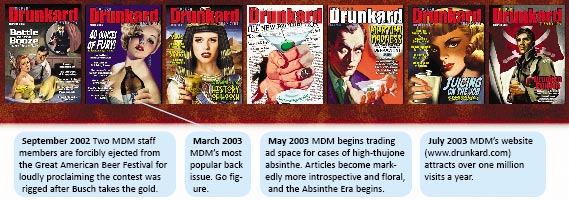

This time around you put up a web site.

One of the smartest moves we’ve made. The Internet is a powerful tool. To reach a lot of people with a print magazine you have to spend a lot of money and put out a helluva lot of issues. With the Internet you can reach millions for practically nothing. And if you’ve an idea with merit, people will listen.

At what point did you stop being a regional magazine and become a national one?

It started with Tower Records. The legendary Clint Johns was at the helm of their magazine division at the time. He was known for encouraging small magazines. He gave us a leg up and a lot of sage advice. We picked up four other distributors and suddenly we were available internationally. Our press coverage blew up. Magazines and newspapers from Germany, France and the UK wanted interviews, foreign film crews came around asking ridiculous questions. We launched offices in Philly and Minneapolis and topped out at 50,000 issues per run.

The Jack Daniel’s boycott also helped put you in the national spotlight.

The media loves a David and Goliath story. The Associated Press interviewed us about backing a boycott of Jack launched by one of our board members, and overnight 50 newspapers were spreading the word that Brown-Forman, the company that had bought Jack, had quietly lowered the proof. For the second time. We publicly shamed them and exposed them as nothing more than a gang of greedy vampires sucking on the neck of a once-great whiskey.

How did the book The Modern Drunkard: A Handbook for Drinking in the 21st Century come about?

We were media darlings at the time. The media is very incestuous—you’re invisible until one influential source points a finger at you. Then they all look in your direction and want to do a story. In a short period we’d appeared on MSNBC, in the LA Times, the NY Times, the Washington Post, La Monde, Time, even The National Enquirer, for crissakes. Suddenly a swarm of book agents started calling. I chose the best of the lot, a fellow drunkard and a fine gentleman, and he immediately sold the idea. Another book, Adventures with Alcohol, is coming out in the Autumn.

So, what do you reckon is around the next bend in the river? El Dorado?

Another waterfall, most likely. It’s the nature of the business. We’ll ride it out this time. What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.

Or maims you.

So? FDR was a cripple, not to mention a drunkard. And that didn’t stop him from whipping up on Tojo and Hitler, now did it?

—Interview by Giles Humbert III